North Fremantle

Garungup, River bend, Derbal Yerrigan, river view, limestone cliffs, seven sisters.

The dramatic site is located at the edge of the narrow neck of land between the bend in the Swan River and Leighton Beach with the Indian Ocean beyond. The site is on the edge of a limestone cliff face that leads directly down into the river at Rocky Bay, providing wonderful uninhibited views down the cliff face to Rocky Bay below and out over the Swan River. Rocky Bay is known by Noongar Peoples as ‘Garungup’, taking its name from a large cave to the western side of the bay which is associated with the Rainbow Serpent ‘which slept there after the great flood that flooded the land between the land and Wadjimup (Rottnest Island).

The house which provides the owners, a retired couple, with a lock and leave lifestyle takes full advantage of the wonderful views both to and from the river. The design of the house features textural limestone materiality which is drawn from the limestone cliffs below. Limestone featured prominently in the Rocky Bay area historically with the ‘Seven Sisters’ hills that once existed in the area now totally removed thanks to the mining of limestone for the construction of many early buildings and for the construction of Fremantle port. It was therefore fitting that limestone featured prominently in this new house upon the cliffs.

The design service provided by Neil Cownie was holistic in the provision of architectural design.

CLIENT BRIEF

Cliff House was designed for an experienced commercial landscape architect who had owned this fabulous site for some time. Neil was asked to provide a conceptual design for this house in competition with one other architect. Neil was successful in winning the competition with this design for the new home. Only on winning the competition did Neil became aware of his unsuccessful competitor, none other than Peter Overman.

Neil’s clients were a retired couple who were looking to create a home that took advantage of the natural beauty of the site. The couple were wanting a lifestyle of ‘lock and leave’ in apartment style living. They also wanted to separately accommodate their adult children to allow them to independently come back to the family house from time to time.

HISTORY OF PLACE AND PEOPLE

Local Indigenous groups utilised the natural resources of the Swan River for over 40,000 years (Pierce and Barbetti 1981). Archaeological investigations demonstrate that Rocky Bay, the traditional name for which is Garungup, has been utilised for 10,000 years (Dortch 1975). Living a seasonally nomadic lifestyle, the Nyungar peoples used a calendar of six seasons that governed when and where they moved to take best advantage of seasonally available resources (Green 1984:10). In the colder months, they occupied the hills to the east of the Swan Coastal Plain, whilst in the hotter months they moved

towards the coast. Aboriginal groups camped on the banks of the rivers and estuaries to take advantage of the cooling winds that came off the waters and from the ocean. Green (1984:11) notes that in “spring and summer fishing was popular in the sheltered bays of Mandurah, Fremantle and Albany, and groups of 20 or more women and children armed with branches drove schools of mullet into the shallows to be speared by the men”. They stayed in these locations for as long as conditions and food allowed (Hammond 1933).

Local traditional owners described Rocky Bay as being a place of significant mythological and ceremonial importance. A large cave on the west side of the bay is called Garungup (from which the bay gets its traditional name) and is associated with the story of the Rainbow Serpent. The cave is believed to be “the place where the Rainbow Serpent slept after the great flood flooded all the land between Wadjimup (Rottnest Island) and the 23 coast” (K. Colbung cited in NFCMCHP 1992:6). This pattern of lifestyle was only interrupted by the permanent settlement of the Swan River Colony in 1829. (Source: Maritime Archaeology – Rocky Bay. Museum WA).

In 1987 Mr Ken Colbung (Chairperson of the Nyungar Community at Gnagara) met the North Fremantle Heritage Trail Committee. At the meeting Mr Colbung explained that he was not the custodian for Rocky Bay, and he would therefore consult Corrie Bodney (the areas custodian) and some other elders for further information. Mr Colbung did say that the cave in front of Burford's Soap Factory in Rocky Bay (northern cave in Figure 5 and see Plate 10) was known as Garungup, and that it was enshrined in Aboriginal methodology as the place where the Rainbow Snake (Waugal) slept after the great flood inundated the land between Wadjimup (Rottnest) and the coast. He explained how you can see where the Rainbow Snake curled around the central pillar of the cave on its journey upriver to its home in another cave near where Bennett Brook meets the Swan River. All the land around Rocky Bay and Buckland Hill is the dreaming place of the Rainbow Snake. Minim Cove was a corroboree ground. There were many watering holes and springs along the river, including one at Minim Cove, one east of Stirling Bridge and another opposite Point Brown in East Fremantle (Ecoscape, 1993).

North Fremantle was established in the 1850s as part of the wider Fremantle area. It was originally a residential area but quickly transformed into a light industrial suburb. In 1895, a petition was made for the area north of the Swan River to split from the City of Fremantle to become the City of North Fremantle (Ewers 1971:101). The landscape of the suburb was also transformed with the quarrying of limestone for the new Fremantle port. By the early twentieth century, North Fremantle became the location of a large number of manufacturing industries that supplied not only the construction of the new port, but also surrounding businesses and households with a wide range of goods. The concentration of all these industries in one place produced a discernible odour that gave North Fremantle the distinction of being called “Pong Alley” (D. Houston cited in Hartley 2008:50).

In 1970-71 G.W. Kendrick recovered several chert flakes (artifacts from tool making) in sand, overlying limestone of the Spearwood age, collected at the rubbish tip site adjacent to Minim Cove (Map 4). An archaeological survey in 1975 discovered two chert flakes in situ at the rubbish tip. Systematic trench excavations found traces of charcoal, quartz chips and a large lens 30 of charcoal, which was radiocarbon dated at between 9,800 and 10,060 years BP, at 70 cm below trench datum. Deeper down, even older chert and quartz chips were found, along with stone artifacts and pebbles. The closest this type of stone is found to Minim Cove is at the Darling Scarp (25 km to the east). This is factual evidence for movement between the Scarp and the area for at least 10,000 years BP. One early settler wrote that families living near the Preston Point ferry would occasionally; 11 ••• see the natives on the opposite side of the water; they used at night to kindle huge fires and dance around in the most fantastic manner, more like demons than anything else. 11 (Robinson, 1987). In 1829, Captain Fremantle reported seeing Aboriginals running along the hill tops to the riverbank between Minim Cove and Point Roe (Ecoscape, 1992).

(Source: Swan River Foreshore Fact Finding - Rocky Bay to Point Roe by Ben Davy - Swan River Trust 1994).

Along the way in 1874 there had even been a scheme to create a channel connecting the ocean to Rocky Bay. The Swan River mouth was once blocked by a large limestone bar which prevented shipping from entering the river. Ships berthed alongside the Long Jetty where goods were unloaded and moved to a smaller jetty on the inside of the river mouth for loading into smaller boats and barges. The Long Jetty and its anchorage were fully exposed to the violent storms of the Indian Ocean, causing vessels to drag their anchors which resulted in more than one vessel being wrecked (see Henderson 2007). The idea of constructing a channel connecting Rocky Bay to the ocean through the limestone bedrock was considered as early as 1829 but was not actively pursued until 1873-4. The feasibility study for the proposal was undertaken by the Reverend C.G. Nicolay, a noted geographer who arrived in the Swan River Colony in 1870 (Playford and Pridmore 1969:31). Other engineers proposed various designs for construction of an external port at the river mouth, as well as for the development of Cockburn Sound, a few kilometres south of the river mouth (Ewers 1971:92). The project was hindered by indecision which continued until 1892 when plans were ultimately settled upon by the new Engineer–in-Chief for Western Australia, Mr C.Y. O’Connor (Ewers 1971:93). 30 O’Connor proposed the removal of the limestone bar and the construction of a deepwater port within the river mouth. The stone for the northern breakwater would be limestone sourced from nearby Rocky Bay, specifically targeting the Seven Sisters formation. Limestone from the hills overlooking Rocky Bay was quarried from the 1870s until the 1960s. It was the primary raw material for many of the early buildings in the colony, particularly Fremantle. However, the volume required for the construction of the port was extensive. Quarrying for the port project began in the early 1890s and finished in 1897. The limestone was transported to the construction site by both rail and barge. A dedicated rail line was built between the quarry and the works, and a jetty was established on the river at the base of Stone Street for loading of quarried stone onto barges (Tuettemann 1991:88). When the port was completed, six of the seven hills had been totally removed and the seventh was severely impacted. A large limestone terrace now exists in their place. (Source: Maritime Archaeology – Rocky Bay by Darren Cooper. Museum WA).

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

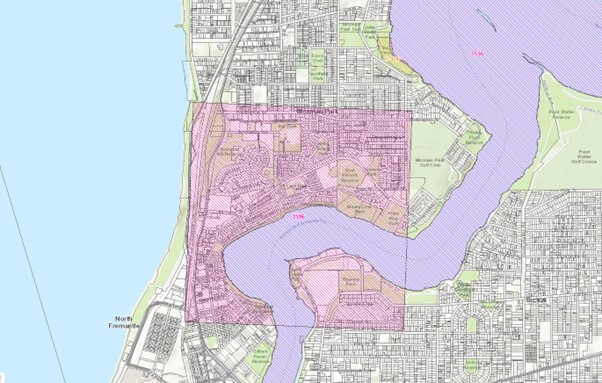

Rocky Bay is located in the Swan River approximately two kilometres inland from the Port of Fremantle. It is a small bay located between Point Direction and Minim Cove. When Europeans first established the Swan River Colony, Rocky Bay was described as “the most beautiful bay in the Swan River with its high cliffs overhung with peppermint trees, cypress pine and many shrubs” (Downey 1971:40). It was overlooked by seven large limestone hills called the Seven Sisters which was the dominant geographic feature in the area. The waters in the bay were clear and abundant with fish, crabs and prawns. The western cliffs and northern embankment are vegetated with peppermint trees and smaller shrubs. Much of the original vegetation has been cleared for development, but would have included tuart (E. gomphocephala), jarrah (E. marginate) and marri (E. calophylla) woodland (Chalmers 1997:4). (Source: Maritime Archaeology – Rocky Bay by Darren Cooper. Museum WA).

The area is part of the Spearwood Dune System which is characterised by an undulating landscape of limestone hills. The most noticeable feature of the pristine landscape is its gently undulating nature dominated by seven large hills known as the 'Seven Sisters'. The 'Seven Sisters' were a significant landscape feature before extensive quarrying began in 1890 and altered the area to its current relief. Buckland Hill was the highest of the 'Seven Sisters' at about 61 metres AHD (now 45 metres). The second largest of the 'Seven Sisters', at about 55 metres, was situated at the intersection of McCabe and Palmerston Streets near T.J. Perrott Reserve. A small unnamed hillock is still present at 42 metres (Reserve 36198).

A ridge of smaller hills extended from here, across the CSBP and SEW sites, to Rocky Bay. These sites are partly located on ground reclaimed by the dumping of quarry spoils into the river, which also considerably filled in, ruined and reformed the northern shoreline of Rocky Bay (Downey, 1971). The SEW and CSBP embankments are now between 10-20 metres AHD. Another unnamed remnant of the 'Seven Sisters' is located within the CSBP site and is now the highest point within the area at 43 metres. (Source: Swan River Foreshore Fact Finding - Rocky Bay to Point Roe by Ben Davy - Swan River Trust 1994).

The pockets of fossil-rich marine shell beds within the Tamala limestone in the Rocky Bay / Minim Cove area said to be of local and national importance with the outcrop said to be the best exposed, best preserved and most informative deposit of its age in W.A. It is also one of few fossiliferous outcrops that occur conveniently close to Perth. Its value to the study and teaching of the history of the Swan River district in the recent geological past is outstanding.

From ‘The site represents one of four separate marine transgressions in the Swan Estuary area during Middle to Late Quaternary times (3-400,000 to 4,000 years BP). The four sites are of national and international significance and lie within a few kilometres of each other in the metropolitan area. The sites include rich and highly diverse fossil remains and are of important palaeontological and stratigraphic significance. The sites are important research areas and have been extensively studied. Results of research are of world-wide significance, and studies are still in progress’. (Source: Swan River Foreshore Fact Finding - Rocky Bay to Point Roe by Ben Davy - Swan River Trust 1994).

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

The site provided dual access opportunities with street frontage both to the north and south sides with almost a full change in floor level between street ground levels. The design took advantage of the changes in level and dual frontages to create two separate entry points, with one serving the retired couple and the other serving their adult children. This then allowed for excellent zoning of use within the house while connection between these zones was provided by the internal stair. While the house is orientated to provide outlook to the east over the river, the living areas on each floor level are provided with an orientation to north ensuring controlled sun protection during the summer months and full winter sun penetration to warm the interior in winter.

As the house is seen from a distance down the length of the river, the house has been designed to have an identity upon the top of the cliff. The building visually comes out of the cliff through the use of limestone as the base material to the exterior of the building. Articulated into a series of components, it is the terracotta shingle roofscape that provides the house with its identity, holding all of the elements together. The external textural materials continue inside where the house reflects the feel of the locality of North Fremantle.

Importantly the design seeks respectfully feature Tamala limestone both internally and externally to relate to the precinct’s geology, Noongar history and European history where the limestone has featured over time.

SUSTAINABILITY

The design of the house orientates to the eastern view which has led to the incorporation of remote-controlled aluminium louvres to the eastern windows to provide sun control. Living spaces are also orientated to enjoy the benefits of a northern aspect to allow the winter sun to penetrate and warm the interior of the building. Tamala limestone features prominently as both a structural and finished element. Limestone as a building material has a low carbon footprint when compared to manufactured materials such as brickwork and concrete. Limestone is also a material that will endure over the long term and can even be salvaged and recycled at the end of the building's lifespan.