Derbal Yerrigan (Swan River)

Swan River, oxygenation, transport, Djarlgarro, shark-proof, Marli, swans, swimming, boating.

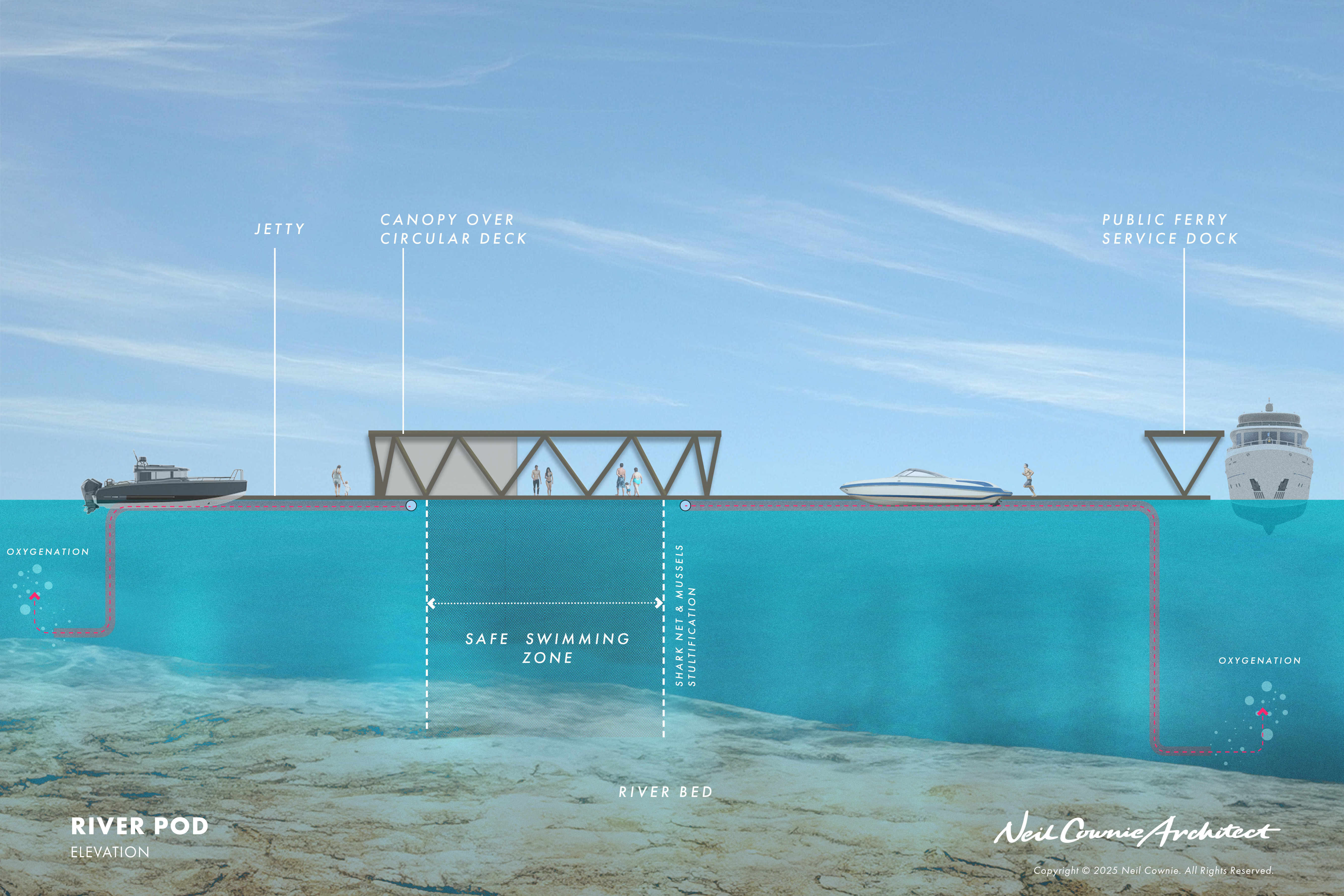

Having experienced the extensive use of rivers and harbours in European cities for public transportation, private boating, canoeing and swimming, it seemed ridiculous that here in Perth with our wide expanse of river, there is no public transport. That experience led Neil to consider what could be introduced in the Swan and Canning rivers to encourage further engagement with our rivers, not only for the benefit of humans, but to also benefit the health of the river system through the cultivation of mussels and oxygenation of the river. The State Government has subsequently announced plans for an eclectic ferry system to serve the Swan River which is to be applauded. The initially released information on the proposed network and ferry stops does seem to miss opportunities to further enhance systems in parallel with the new benefits that the proposed ferry service will bring. Neil's River Pod concept shows the benefits that a multifaceted design approach can bring.

The design service provided by Neil Cownie included speculative architectural design for the purposes of advocating for river health and river transport.

This scheme is under copyright by Neil Cownie Architect.

Client Brief

There was no client as such as the ‘River Pods’ concept was a speculative exploration of Neil’s own doing to find opportunities to engage with our river and to improve the health of the river system.Since the commencement of Neil’s speculative conceptual study several years ago, the Western Australian Government has now set the Public Transport Authority the task of engaging industry to construct five electric powered ferries that will form the beginnings of a Swan River public transportation route. It is currently proposed that ferry stops will be created at Applecross, The University of Western Australia and Elizabeth Quay. Over time additional ferry stops may be created at Point Fraser, Burwood Park, Optus Stadium and Claisebrook.

History of Place & People

The following information has been sourced from the ‘Marli River Park document – An Interpretation Plan. Swan River Trust – 2014’ - Noongar cultural ideologies, language and social mores have been based on the same tenets since kura kura, a long time ago and are transmitted and maintained via stories. While the content of these stories may change in accordance with the narrator, location and audience, the Waakal (Waugal, Wagyl, Waugyl, Wagul etc.) or Noongar Rainbow Serpent is commonly depicted as the creator.46 Many Noongar consider the Swan-

Canning Riverscape sacred due to stories associated with the Waakal and its continued presence in the area. Noongar Elder Everett Kickett theorised that the Waakal created the Derbal Yiragan, which means where the estuary is filled up by the winding river, now known as the Swan River.

Furthermore, Noongar Elder Ralph Winmar wrote that the Waakal made all ‘rivers, swamps, lakes and waterholes’. If one were to look at Derbal Yiragan (as the Perth waters of the Swan River) from the top of Kaart Djinanginy Bo, or Mount Eliza (Kings Park), it would be easy to visualise this huge Waakal twisting and turning as it made its way to the coast. Noongar Elder Albert Corunna said, during the Dreamtime the Waakal ‘moved across the landscapes of Perth and as he moved the waterways were created which included the Swan River’. He explained, ‘(t)his is the way the rivers were made as told by my old people'. (Source: Marli River Park).

The Dutch mapped the Swan River in 1697 but did not explore the Canning. The first Europeans to report seeing the Canning River were the French in June 1801. A party from Nicholas Baudin’s Naturaliste led by Heirisson first explored the Swan,

encountering difficulty at the ‘flats’ which they named Heirisson Islands. They then turned their attention to the Canning River entrance they called Entrée Moreau, after a member of their party, midshipman Moreau. They did not explore further but

commented that it probably linked with the sea. The first Europeans to explore the Canning River, so named by Captain Stirling, was a small team from the party on their return from the journey along the Swan in 1827.

Lyon’s 1833 map of Aboriginal groups around Perth has the Canning River as Munday’s Beelo territory on the north of the river with Midgegooroo’s Beeliar territory to the south. These groups feature prominently in the early European exploration and settlement of the Canning River.

The river provided rich resources for the various groups as they travelled through and camped in the area. Early European explorers noted a widespread Aboriginal presence and relationships were relatively friendly. The waters of the Canning provided rich resources for the Noongar people in the area and the banks provided materials for everyday life. The area was one of significant activity for Aboriginal people with intense movement along the riverside tracks and across the landscape.

The Swan River Trust engaged with a consultant team, the National Trust a Noongar advisory Panel along with other esteemed contributors to create a vision for the Swan River and its surrounds. This final document is a fabulous source of information and considers so many aspects of the rivers history and physical make up as it proposes that in its entirety the precincts of the Swan River and Canning River would be known as the Marli River Park. The creation of marli riverpark is the major guiding and transformative initiative of the Interpretation Plan. marli, marlee, maali, marley is the Noongar for Swan (Cygnus atratus), The name 'marli' signals significance above, below, in and on the riverscape. The use of lower case 'marli' signals ‘not’ using the English conventions and grammar. We do not speak or listen in capitals hence marli signals a spoken and audio [listen] communication, not a written one.

‘The river’ by Jennifer Kornberger, 2013

This river once had a mouth that opened and closed.

A mouth with limestone teeth and a tongue of sand.

The first rains woke it from its estuarine sleep, loosened its tongue, so the mixing, the darbaling could begin.

When rainbows became scarce the river sealed its mouth, it curled back and listened

to the thousand voices informing it.

A river lives between course and discourse. It has business, the office of its whole catchment to fulfil.’

There is a history of bathing in the swan river with opportunities for formalised bathing previously available at the Claremont Baths, Matilda Bay Baths, and Perth City Baths. With all of these bathing pavilions now long gone, this concept for the ‘River Pods’ provides opportunity for safe bathing in the river once again.

Landscape & Geology

The meandering path of the Swan River takes many a curved turn in almost circular bays such as that at Fresh Water Bay and Matilda Bay to name but two. In such bays, what is now part of the river was historically potentially swampland adjacent to the river which over time the river eroded the buffer between to become scoured out the swampland to become part of the river.

Today there are interesting natural circular contained river edge bays such as that at Salter Point Lagoon and formerly at Mill Point (or Point Belches) prior to the construction of the Narrows Bridge. From historic photos the beautiful naturally circular body of water was known by Noongar people as Kaneenup before named Millars Pool by the European settlers. From the museum of Perth - ‘Kareenup’ – ‘This area is referred to as the place of Kareen, a prominent Noongar and the brother of Beenan. Both regularly camped at the peninsula tip in the ninteenth century, which was inherited from their father. While Kareen favoured the Buneenboro (Perth Water) side near the present-day South Perth foreshore, Beenan preferred the Melville Water side along the Canning River. Kareen’s favourite camp encompassed what is now known as Miller’s Pool. The Pool was connected to Buneenboro and fed by a nearby freshwater spring on the Melville Water side of the peninsula. Banksia grew abundantly in this area and was Beenan’s totem. Each year during the season of Kambarang (October-November), large communal gatherings for ceremony, trade, and hunting occurred within the two brothers’ area.

During Kambarang, the flowering cones of banksia began producing nectar. Noongar taboo prohibited banksia consumption before Kambarang, and Noongars would watch for cockatoos and honey possums to begin consuming banksia cones as indicators that they were ready to gather. The Noongars would have used kalgas (a long, hooked stick) to pull down the higher cones from banksia trees.

Once gathered, local Noongars would widen Kareen’s freshwater spring and throw the honey-bearing mungaitch (banksia flowers) into the spring for several days of fermentation. This resulted in a light, alcoholic drink which was sweet and mead-like. The brew was shared with their neighbouring kallipgur (kin), who would visit the area from as far away as the Murray district to camp, eat and drink together in celebration of the warming season.

Adjacent to Kareenup was the site of Goorygoogup - an area filled with bulrushes that would be near Shenton’s House and Mill today. Goorygoogup was a birthing area that would have been more secluded and offered privacy away from the popular gathering site of Kareenup.

Despite much local protest, Miller’s Pool was filled and the shoreline of Kareenup was enlarged through reclamation and dredging activities in the late 1930s. This was done to deepen the river at the Narrows and begin the roadwork that has developed into the Kwinana Freeway that stands there today. In 2016, Miller’s Pool was restored and upgraded to its former status as a key foreshore feature.’

From the City of South Perth – The Story of Goorgygoogup (Millars Pool)’ - Goorgygoogup, also referred to as Millers Pool is a place of great significance to the Noongar people. The natural pool was located near Booryulup (close to Richardson Park) and Beenabup (Como Beach). This was a site for women to safely give birth while being protected and cooled by the tall rushes and clean water flowing in from the river.

William Kernot Shenton saw the potential for the pool to aid his milling operation, and a spur channel was dug from the pool to his mill, allowing boats easy access to offload grain. In 1896 the pool took on another life as a wildlife sanctuary. Worried that the black swan was becoming extinct, the colonial government built a fence around the pool and offered a bounty: any healthy swan presented to Constable Rewell of the Water Police was worth a guinea. Though housing hundreds of swans and operating until 1914, the Millers Pool Swannery failed to produce a breeding population. The pool was a controversial feature, considered both a valuable natural landmark and a mosquito-infested eyesore. It was finally destroyed in 1938, filled in with silt gained from dredging ferry channels through the Narrows.’

The geology of the Swan Coastal Plain consists of deep layers of sediments and sedimentary rocks dating back to the Cretaceous Period, 146-65 million years ago.

The youngest of these, from the Quaternary Period (2.6 million years to the present), are intersected by the Swan and Canning River systems and are visible along the riverbanks and estuary foreshores. Interestingly, this period also saw the evolution of the human race and the eventual habitation of the Coastal Plain by Aboriginal people. The Quaternary is described as “characterized by a series of large-scale environmental changes that have profoundly affected and shaped both landscapes and life on Earth”, with an estimated 30-50 glacial cycles occurring.70 Over 40,000 years, Aboriginal people saw the effects of at least one glacial cycle with the rising and falling sea levels and warming and cooling climates which resulted in the Swan and Canning systems as they existed at the time of European settlement.

Around 20,000 years ago, sea level was about 130m below today’s level, Rottnest was just a hill, and the Swan River met the ocean somewhere to the north-west of that hill. By 7,000 years ago, Rottnest was still connected to the mainland, but only just. Sea levels peaked around 5,000 years ago and have since fallen a few metres to the current level. The former Swan and Canning River valleys have been largely flooded by the ocean and filled with sandy and muddy sediments to become the Swan Canning Estuary.

The Swan and Canning Rivers support a diverse array of plant and animal life. There are over 130 species of fish that utilise the estuary including herring, cobbler, mullet, black bream, whiting, crustaceans (including two species of prawns), bottlenose dolphins, long-necked turtles, frogs, seahorses and at least two species of jellyfish. Birds include waterbirds dependent on wetlands for feeding, resting and breeding as well as those migratory species that visit each year. The most well known birds on the rivers are black swans, four species of cormorants, herons, darters, pelicans, ducks, ibises and egret.

The black swan/marli is now the symbol of the Swan River. Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh surveyed and named the river Swarte Swaene-Revier in 1696 when his exploration party saw many of the birds. In reporting on his journey up the Swan

River with Captain Stirling in 1827, botanist Charles Fraser described in some detail the abundant bird life around Point Fraser and the sustenance it provided: The quantity of black swans, ducks, pelicans and aquatic birds seen on the river was truly astonishing.

Without any exaggeration, I have seen a number of black swans, which could not be estimated at less than five hundred rise at once, exhibiting a spectacle which,

if the size and colour of the bird be taken into account, and the noise and rushing occasioned by the flapping of their wings, previous to their rising, is quite unique in

its kind. We frequently had from twelve to fifteen of them in the boats, and the crews thought nothing of devouring eight roasted swans in a day.

(Source: Marli River Park document – An Interpretation Plan. Swan River Trust - 2014).

Bull sharks (or River Whaler) grow to a length of about 3.4m and are the only shark species known to stay for extended periods in freshwater. A Bull Shark is thought to have been responsible for at least one death in the Swan River but there have been several attacks, and the sharks have been caught as far upstream as the Maylands Yacht Club.

Low oxygen levels are another issue with which the Swan River Trust is grappling. The major cause is the microbial breakdown of organic matter. Organic material such as leaves and algae enters the river system, and naturally occurring microbes use oxygen to

break down the matter. Oxygen levels can often drop quickly as the microbes respond to organic matter loading events, particularly in warm weather. In some cases, when the saltwater moves in a wedge from the estuary mouth at Fremantle during the summer, water at the surface of the river does not mix with the saline water which is heavier and sinks to the bottom. Microbial activity in the salty bottom water continues to consume oxygen, but this oxygen does not get replenished from surface water. As well as dealing with the issues of the organic and nutrient load entering the system, the Swan River Trust monitors water quality and has a short-term solution to deal with the issue. The

oxygenation program provides oxygen to targeted areas of the river through four oxygenation plants; at Caversham and Guildford on the Swan River, and two plants upstream of the Kent Street Weir on the Canning River.

(Source: Marli River Park document – An Interpretation Plan. Swan River Trust - 2014).

Architecture & Design

The concept for the ‘River Pods’ has grown from the original intention of providing the public with multiple safe places to swim in the river whereby there was also ‘give back’ to the health of the river system. Over time this concept has grown to include safe places for boats to temporarily dock and for public river transport.

The River Pod concept now consists of a series of components that can be added or subtracted from any location depending on the locations demands and suitability.

The components consist of:

RIVER SWIMMING POD

The swimming pods can be upscaled depending on their location with the base model providing a safe 25-meter diameter swimming area surrounded by a shark-net. A perimeter decking area allows space to sunbathe and for shade structure. The pod also hard working for the environment with solar PV cells to the shade structure which power aeration of the water to improve the health of the river system. The shark-net also allows for marine life habitation for mussels to grow which provide opportunities for school groups to snorkel and to be educated about the river system.

RIVER TRANSPORTATION POD

The transportation pods cater for the State Governments proposed new river ferry service. These pods can be secured after hours, provide ticketing, shelter from wind rain and sun, provide seating and docking for the electric ferries. The roof contains solar PV cells for lighting and potentially to contribute to the power and recharging of the ferries while docked. Jetties connecting to the pod contain baffles to minimise the impact of the wake from the ferries on the shoreline. The space between the jetty and the shoreline is intended to be revegetated to create natural habitats for bird and marine life. Like the River Swimming Pods the Transportation Pods will aerate the water to improve the health of the river.

RIVER DOCKING POD

Temporary docking is provided for small boats at the River Docking Pods which cater for private boat owners. These Docking Pods further enhance the use of the river as a means of transport. These pods will also provide power through solar PV cells on the roof shelter for the aeration of the river, for lighting and for boat users.

There is a history of bathing in the swan river with opportunities for formalised bathing previously available at the Claremont Baths, Matilda Bay Baths, and Perth City Baths. With all of these bathing pavilions now long gone, this concept for the ‘River Pods’ provides opportunity for safe bathing in the river once again.

This concept for river pods is intended to provide a safe place for river swimming centrally to the pods protected via a shark-net, while the perimeter provides opportunities for boats to moor. Private boats could temporarily pull up to the pods in a similar way as is possible at Elizabeth Key for a limited amount of time. To ensure that the pods are egalitarian, there is a larger docking opportunity that is intended for a river taxi service to provide access to the pods for everyone. A series of these pods are proposed for locations along the river where they are more protected from the cold afternoon sea breezes. There is potential for a food and beverage boat to service each pod on rotation to provide food and drinks to those spending time on a river pod.

These pods would not only serve for exercise and entertainment, but they would also benefit the river system through being a source of oxygenation and mussel cultivation.

When Neil was first in Copenhagen, he became aware that the boardwalks that ran alongside and into the harbour were the main structure for the netting that contained the cultivation of mussels. Local school children were introduced to the cultivation and harvesting of mussels in small groups of snorkelling excursions below the boardwalks. We too have opportunity to recreate such an experience. The mussels filter out nitrogen and phosphorus from the water, two substances that cause serious problems in terms of marine eutrophication. However, as long as the mussel biomass remains in the water, they provide no net effect. The filtering benefits of the mussels can be increased if the mussels are consequently harvested. By cultivating mussels, we are not only ensuring cleaner water due to their filtration process, but we are providing opportunity to provide a food source for our community. A regenerative process that can co-exist with the other functions of the proposed River Pods. Neil’s scheme provides a protective shark net to the perimeter of the circular boardwalk component of the design. This netting also serves as the trellis for the cultivation of the mussels.

These proposed River Pods also provide opportunity to artificially oxygenate the river through oxygenation plants that would be located below the pod decks with potential for the oxygen outlets at low river bed levels at the outer edge of each jetty.

From the WA Department of Water and Environmental Regulation: ‘Low oxygen concentrations is a symptom of excessive nutrients entering waterways from surrounding urban and agricultural land - a process known as eutrophication. Excessive nutrients can accelerate the growth of aquatic plants and algae, which consume oxygen over-night when they respire, as well as through degradation processes when they die. Oxygen is also consumed by chemical reactions occurring in the top layers of the sediment.

Oxygen is naturally replenished by transfer from the overlying air, mixing (via wind or flow) and the photosynthesis of aquatic plants and algae during the day. However, in highly eutrophic systems, oxygen is consumed faster than it is replenished, and concentrations decline, sometimes to the point the water body is completely devoid of oxygen.

Oxygen is essential for most aquatic life. Low dissolved oxygen impacts on the healthy functioning of the ecosystem and may cause acute stress and death to marine life. The Department of Water and Environmental Regulation began trialling artificial oxygenation to supplement excessive oxygen demands and mitigate the symptoms of low oxygen in 1998–1999 both with a land-based plant on the Canning and a barge-mounted plant on the Swan. The success of trials led to artificial oxygenation becoming a long-term management tool for the Swan-Canning estuary. Four oxygenation plants are now managed and operated by Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, two on the upper Swan at Guildford and Caversham, and two on the Canning River above the Kent St weir at Bacon St and Nicholson Rd.’

Sustainability

The proposed series of River Pods provide opportunities for the WA Department of Water and Environment Regulation to expand their points of oxygenation to the Swan & Canning Rivers. River health can be improved further through the cultivation of mussels for harvesting within the perimeter of the River Pods.

Solar PV rooftop panels to the canopy will provide the energy for the oxygenation system. The River Pods also provide educational opportunities for school children to experience the mussel cultivation and harvesting. River Pods located adjacent to the riverbanks at potential ferry stops would also include baffles to reduce ferry wake and encourage zones where natural habitat can be reintroduced thereby benefiting the rivers bird and marine life.