Rottnest Island

Respect, Traditional owners, geology, caverns, salt lakes, limestone, egalitarian, competition.

This scheme for the Rottnest Island Lodge was designed in competition for the Rottnest Island Authority. While our submission was unsuccessful, we believe that our submission was not only appropriately culturally sensitive, but also reopened historic sightlines, brought opportunities for egalitarian access to the site while being commercially viable.

Our design respects, acknowledges, reflects and interprets the cultural and spiritual connection of the Whadjuk People to this place. Our design celebrates the Noongar Songline Jippi Jopy Boodja meaning “Rhythm of the Land”, which is the story of physical and spiritual connecting Wadjemup to all ceremonial and sacred sites across our country. The Songline conceptually connects the significant locations of Strickland Bay, Wadjemup Hill to Uluru, while also passing straight through the Lodge Redevelopment site. We respected and celebrated the pathway of this Songline through the central area of the site where we have applied the concept of ‘landscape as primary and buildings secondary’.

The competition held by the Rottnest Island Authority was open to invited hospitality groups and their selected design teams. Neil Cownie provided the architectural design service within the framework of a design team that comprised fellow design architects Suzie Hunt and Richard Manser, along with Landscape architect Andrew Baranowski and cultural adviser Karen Jacobs.

CLIENT BRIEF

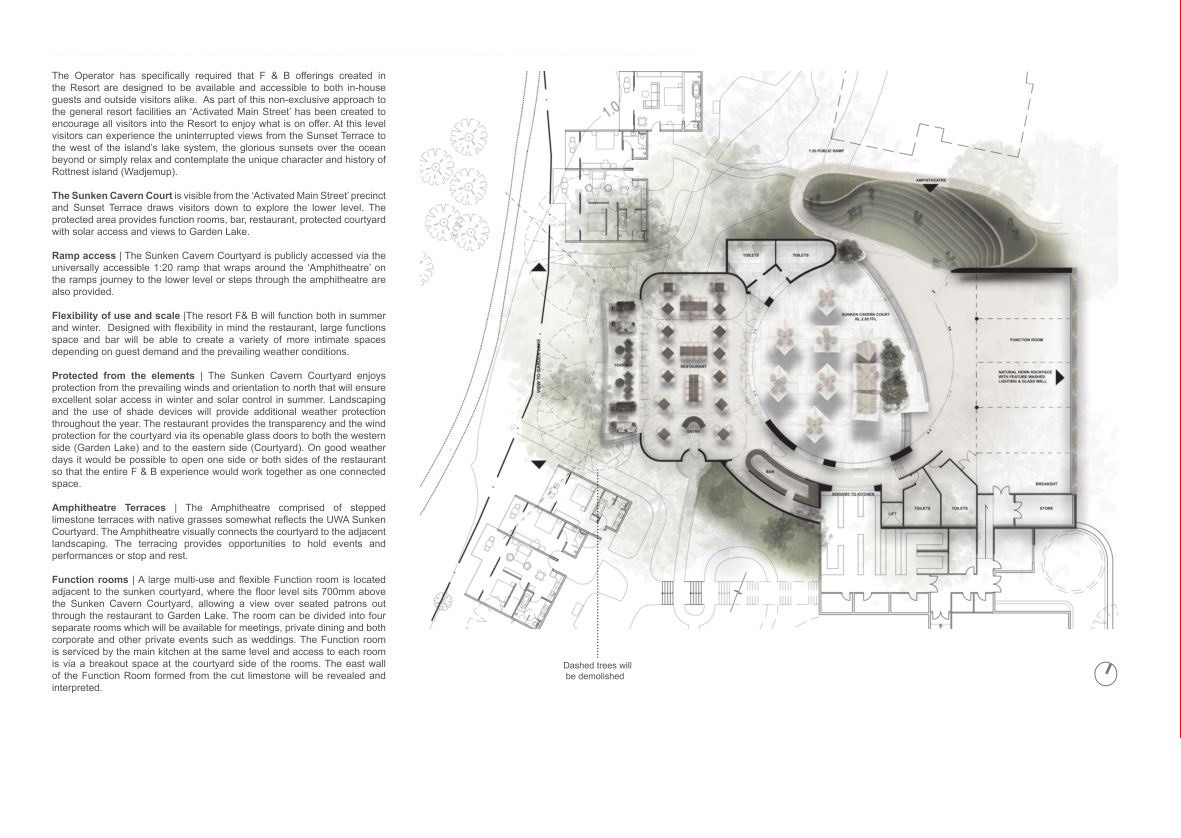

Our Western Australian based client team comprised experienced members from hospitality, finance, and marketing. Our brief was to provide a hotel with 120 rooms comprised of varying standards and price points for egalitarian end use. Facilities were to include a pool area with associated poolside hospitality, functions rooms and critical to the project’s viability was the provision of bars and restaurants that were accessible not only to the hotel guests but also to all island visitors.

With the success of any project coming down to teamwork, our design team were concerned at first that our client team may not engage positively with the essence of our first design presentation, being firstly a powerful response to the cultural and geological significance of the site in what is a commercial project. About twenty minutes into our forty-five-minute presentation, one of the members of the client team stood up and interrupted our presentation to announce to the remainder of the client group that this design was outstanding and that they must back the design one hundred percent. We were firstly amazed and then overjoyed that we had their full support. This project from that moment on was one in which it was complete teamwork from top to bottom where all members were giving everything they had in the hope that we could bring this most respectful scheme into fruition.

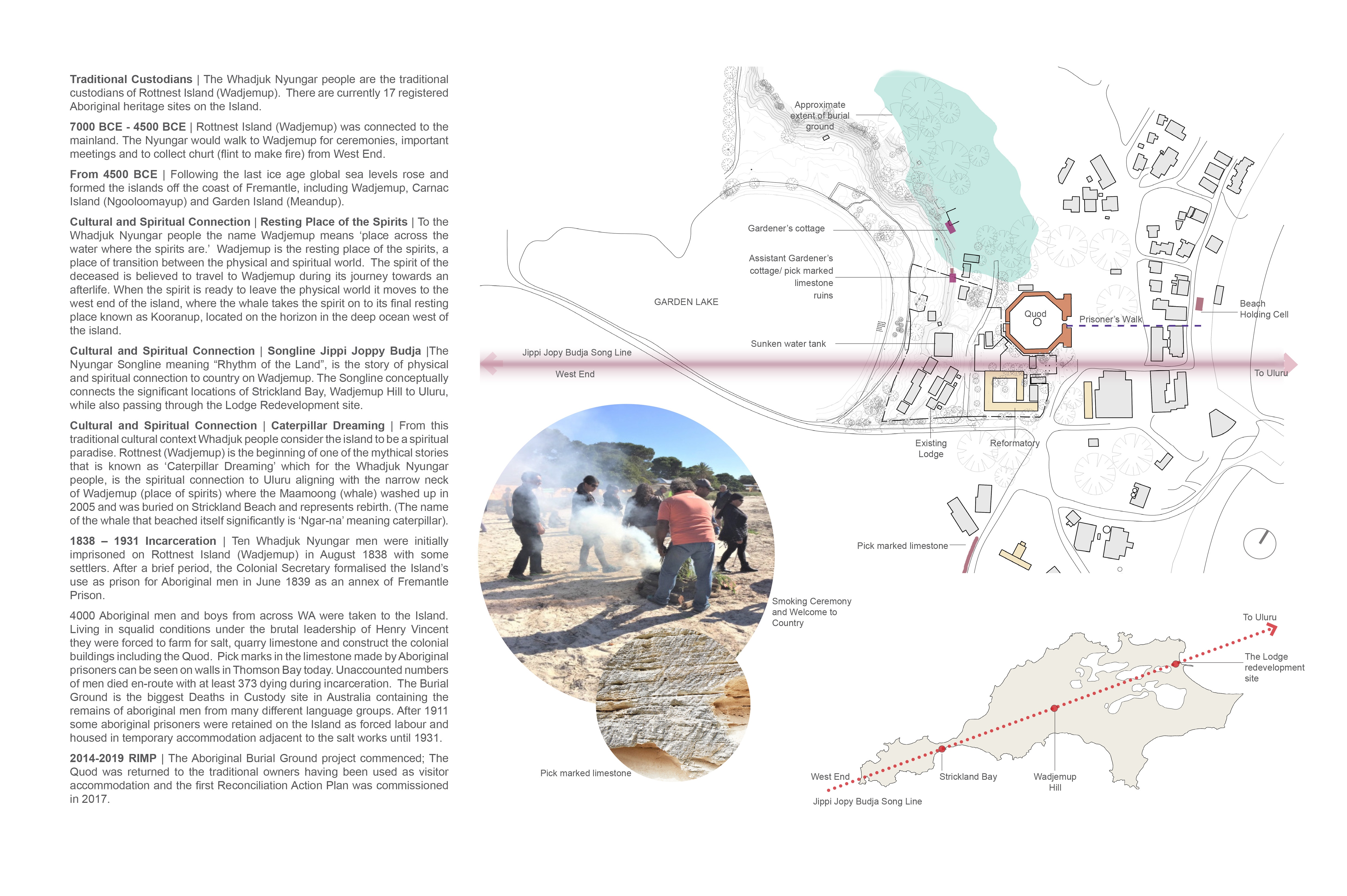

HISTORY OF PLACE AND PEOPLE

Wadjemup [Rottnest Island] lies in the Indian Ocean, 18 kilometres west of Fremantle in south-west Western Australia. The Island is 11 kilometres long and 4.5 kilometres wide at its widest point with a land area of 1,900 hectares and the largest of a chain of islands and shoals on the continental shelf near Perth. Wadjemup has exceptional aboriginal, geological, and ecological significance dating back 130,000 years. The traditional custodians of Wadjemup are the Whadjuk Nyungar people.

Connected to the Mainland | Approximately 6,000 – 7,000 years ago, Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) was connected to the mainland, at that time Whadjuk and other Nyungar people could walk to Wadjemup for ceremony and as an important meeting place. Following the last ice age global sea levels rose and formed the islands of the coast of Fremantle, including Wadjemup, Carnac Island (Ngooloomayup) and Garden Island (Meandup).

- Cultural and Spiritual Connection | Resting Place of the Spirits | The name Wadjemup means ‘place across the water where the spirits are.’ To the Whadjuk people Wadjemup is the resting place of the spirits, a place of transition between the physical and spiritual world. The spirit of the deceased is believed to travel to Wadjemup during its journey towards an afterlife. When the spirit is ready to leave the physical world it moves to the west end of the island, where the whale takes the spirit on to its final resting place known as Kooranup, located on the horizon in the deep ocean west of the island. An extract from a text in the 1914 edition of ‘The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland’ recites the following story, ‘When I die, I shall go down through the sea to ‘Kur’an’up, where all my people will be waiting on the shore with meat food, my mother and my woman, my father and my brothers’(Bates, D.M. 1914, ‘A Few Notes on some South-Western Dialects’).

2. Cultural and Spiritual Connection | Songline |The Nyungar Songline of Jippi Joppy Budja, meaning “Rhythm of the Land”, is the story of physical and spiritual connection to country on Wadjemup. The Songline conceptually connects the significant locations of Strickland Bay, Wadjemup Hill to Uluru, while also passing through the Lodge Redevelopment site.

- Cultural and Spiritual Connection | Caterpillar Dreaming | From this traditional cultural context Whadjuk people consider the island to be a spiritual paradise. Rottnest (Wadjemup) is the beginning of one of the mythical stories that is known as ‘Caterpillar Dreaming’ which for the Whadjuk Nyungar people, is the spiritual connection to Uluru aligning with the narrow neck of Wadjemup (place of spirits) where the Maamoong (whale) washed up in 2005 and was buried on Strickland Beach and represents rebirth. (The name of the whale that beached itself significantly is ‘Ngar-na’ meaning caterpillar).

Incarceration | Almost a century of Aboriginal incarceration on Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) began when the first ten Aboriginal prisoners were brought to the Island in August 1838. After a brief period when settlers and prisoners occupied the Island, the Colonial Secretary formalised the Island’s use as a penal establishment for Aboriginal people in June 1839 as an annex of Fremantle Prison. This became the first and only place in Australia of mass segregation of Aboriginal people from all over WA in a racially determined prison. Approximately 3,700 Aboriginal men and boys from across Western Australia were sent to the Island over this period, over 373 of whom died during their incarceration and are buried in the ground to the north of the Quod. The Burial Ground is unique as it is the only known site in Australia to contain the remains of aboriginal people from many different language groups. It is the biggest Deaths in Custody site in Australia.

Obscured Use | In 1907, a scheme for transforming Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) from an Aboriginal penal settlement to a recreation and holiday Island were drawn up by the Colonial Secretary’s Department. The former prison buildings were absorbed into this new use, including the Quod which was converted for use as holiday accommodation in 1911. Over time these developments largely obscured their former use. After 1911 aboriginal prisoners remained on the Island in reduced numbers when they were housed in temporary accommodation adjacent to the salt works until 1931.

Since the 1600’s the island has been a place of interest for European explorers from the 1600’s (Dutch), 1700’s (French) and the British from1800’s following settlement of the Swan River Colony.

Since the early 19th century, the island has been a popular tourist destination, internment camp during both World Wars and in 2020 a Covid-19 Quarantine Centre.

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

The geology makes Rottnest special. Rises and falls in sea levels have left rocky headlands and numerous sandy beaches that are protected by fringing reefs. Collapsing caves have created unique lakes and interesting landscapes. The soft easily-worked limestone encouraged pioneers to build substantial buildings on firm ground that stand proudly today.

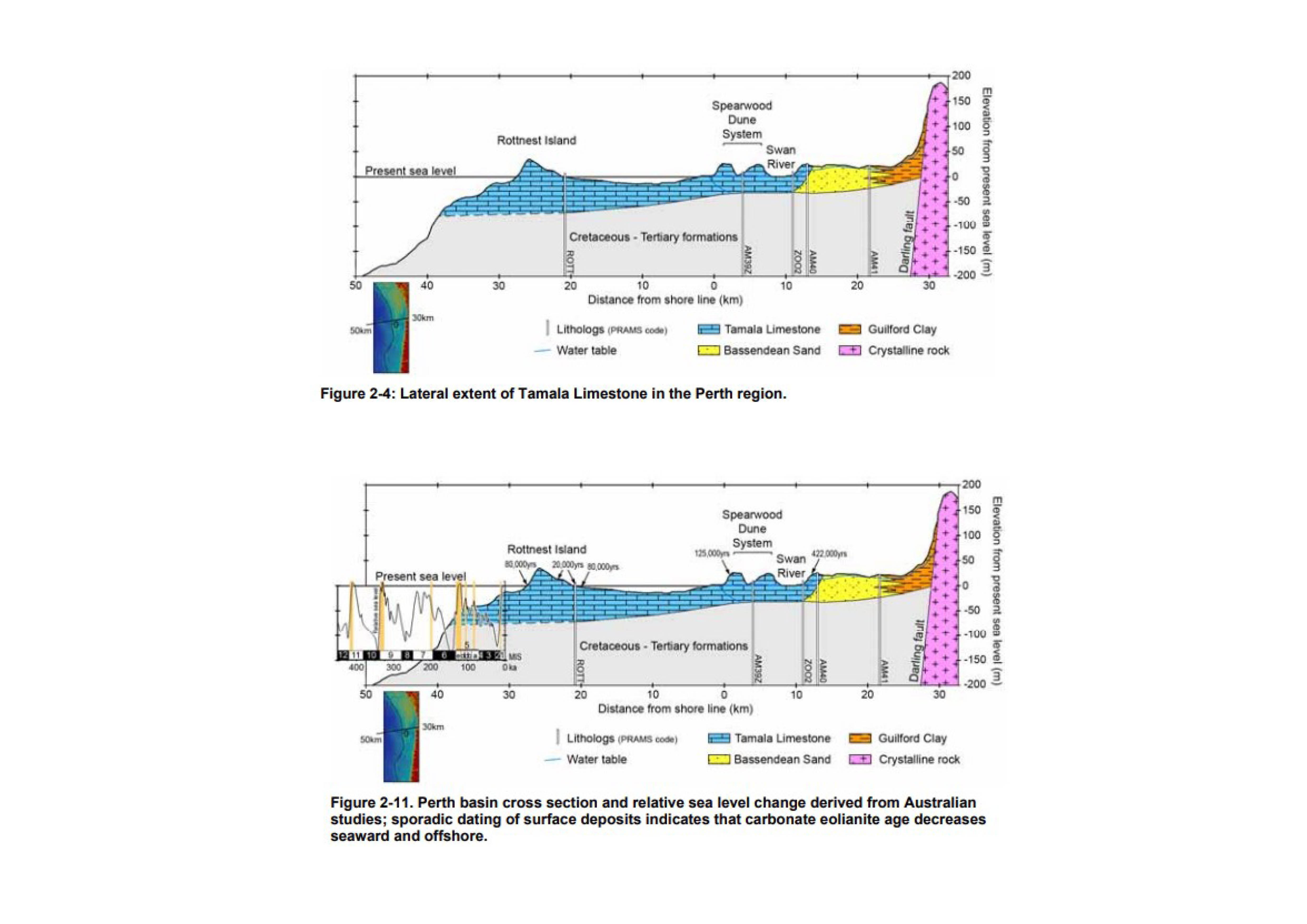

20,000 years ago | Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) formed part of the mainland when the sea level was approximately 130 meters lower than it is today. At that time the island was a high point with Wadjemup Hill being the highest point on the coastal plain and the mainland coast being 20 kilometres to the west of Rottnest.

7,000 years ago | The sea levels rose to about 5–10 meters below where they are today. Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) formed the tip of a peninsular. The former coastlines from this period are evident as off-shore reef systems in aerial photos taken to this day.

5,000 years ago | The sea level was approximately 2-3 meters above where it is today which saw the island separated into an archipelago of around ten islands. The West End was separated from the rest of the island at Narrow Neck and the salt lakes were part of a marine system.

Wave Cut Platforms | Elevated marine features, which indicate sea level changes include fossil coral, shell beds, and wave cut platforms are of international importance in the study of archaeological and geological significance and sea level and climate variations.

Salt Lakes + Underground Caverns | The salt lakes, which form around 10.5% of the island, are unique and thought to have originated as large calcareous dunes collapsed into underground caverns. They are very deep in some places and result in complex hydrology which is evident when studying the contours at the perimeter of the salt lakes, especially with regard to Garden Lake.

Thrombolites | A thrombolite (literally, ‘layered rock’ looks like a cauliflower) are built by micro-organisms (algae and bacteria) that photosynthesize and precipitate calcium carbonate (limestone), which creates the dome shaped thrombolites. Western Australia’s ancient and stable geology and abundance of microbialites is considered one of the most important research areas on the origin and evolution of early life on Earth. On the north side of Government House Lake, the thrombolites grow in lake water up to 3m deep, and are 10 cm high, sometimes 20 cm high, with growth rates of about 1.5mm/year. Fossil thrombolites along the shoreline at the western end of Serpentine Lake are about 2000 to 3000 years old.

Limestone | The Island is composed of three major recent geological units: Holocene (less than 10,000 years) coastal sand dunes; Holocene swamp and lake deposits; and Pleistocene Tamala limestone and lime sand dunes (up to 1.7 million years old). Tamala Limestone, formed by cementation of coastal windblown dunes when the sea level was 130 meters lower than today’s sea level, forms the base to the Island. Tamala Limestone has been the subject of numerous significant studies relating to sea level change because of the unique tectonic stability of Western Australia.

Diversity In Landscape | There is diversity in the landscape and resulting flora through the island such as the ‘sea rocket, spinifex and aromatic wild rosemary of the coastline, the tussock grass, prickle lily and the Rottnest daisy of the grasslands, the Rottnest Pine, Rottnest Tea Tree and scented wattle of the woodland and the salt tolerant flora such as the Samphire, Broad Leaf Grey Saltbush and Sedges of the salt lakes.

Flora | Prior to separation from the mainland, Wadjemup would have had a similar range of plants as those on the adjacent mainland. Exposure to sea water, salt and wind eliminated hundreds of species so that today there are only about 140 indigenous species left on the island.

Biodiversity | The various benthic microbial communities or algal mats are the dominant primary producers in most of the coastal lakes. The biodiversity of these systems is significantly linked to a large variety of avian fauna including migratory birds. The microbial mats in the salt lakes of Rottnest Island are dominated by cyano-bacteria and diatoms. These microbial communities in Rottnest Island salt lakes reflect the water quality, nutrient status and the interactions between biota and the physicochemical environment

Microbiolites | The significant hypersaline microbialite communities of the salt lakes are listed as Priority Ecological Communities (PEC) under State Legislation. These microbialite communities are unique to the south-west of Western Australia. Various benthic microbial communities or algal mats are the dominant primary producers in most of the coastal lakes and reflect the water quality, nutrient status and the interactions between biota and the physicochemical environment. The biodiversity of these systems is significantly linked to a large variety of avian fauna including migratory birds. The lakes during summer will expose many colours from pinks, greens, blacks and even oranges; these colours reveal the secrets of the lakes hidden beneath the water and are the active microbial mats. These mats are communities of organisms which inhabit the floor, and under the right conditions deposit limestone in the form of microbialites. They are highly valuable biodiversity assets as each community is unique and are modern equivalents of the earliest life forms on Earth.

Water supply | Water supply to the freshwater seeps and brackish swamps occurs through rainfall and ground water. These areas provide critical breeding habitat for three species of frog which are morphologically distinct to those on the mainland.

Fauna | The island supports fauna species that are significant at local, federal and global scales, including the Quokka, Osprey, shorebirds, bush-birds and genetically distinct reptiles. The recent exponential increase in numbers and diversity of migratory birds to the Rottnest salt lakes is due in part to the increased development of the Perth coastal plain.

The Butterfly | There have been seventeen species of butterfly recorded on the Island, some of which are residents; living and breeding on the Island: others are transient from the mainland. The butterfly forms an important part of the Whadjuk Nyungar mythical story known as ‘Caterpillar Dreaming’, which tells the story of Wadjemup being a ‘spiritual paradise’.

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

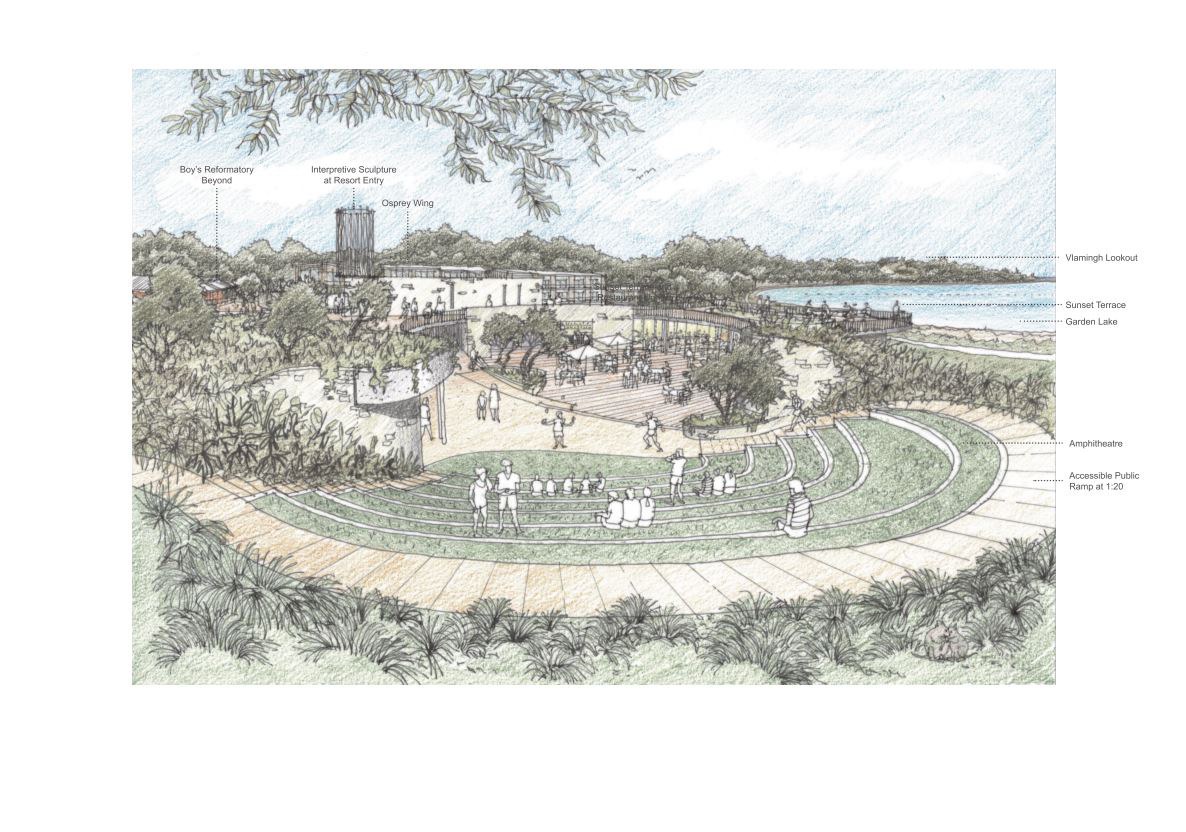

Our design embraces the elements of the incredible geological history of the Island. The rises and falls in sea level have left rocky headlands and numerous sandy beaches that are protected by fringing reefs. Collapsing former caverns have created unique Salt Lakes and interesting landscapes. The soft, easily worked limestone encouraged pioneers to build substantial buildings on firm ground that stand proudly today.

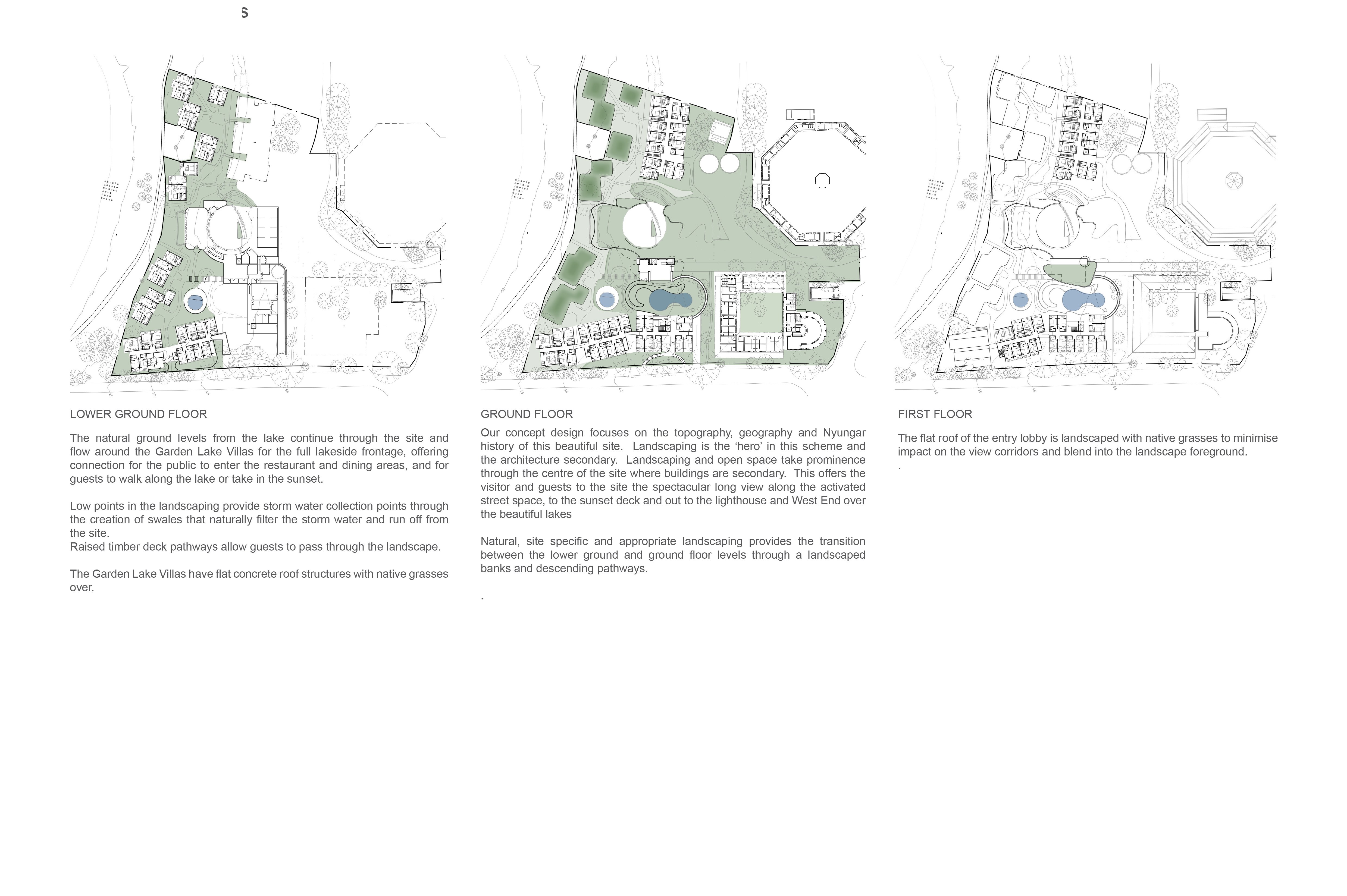

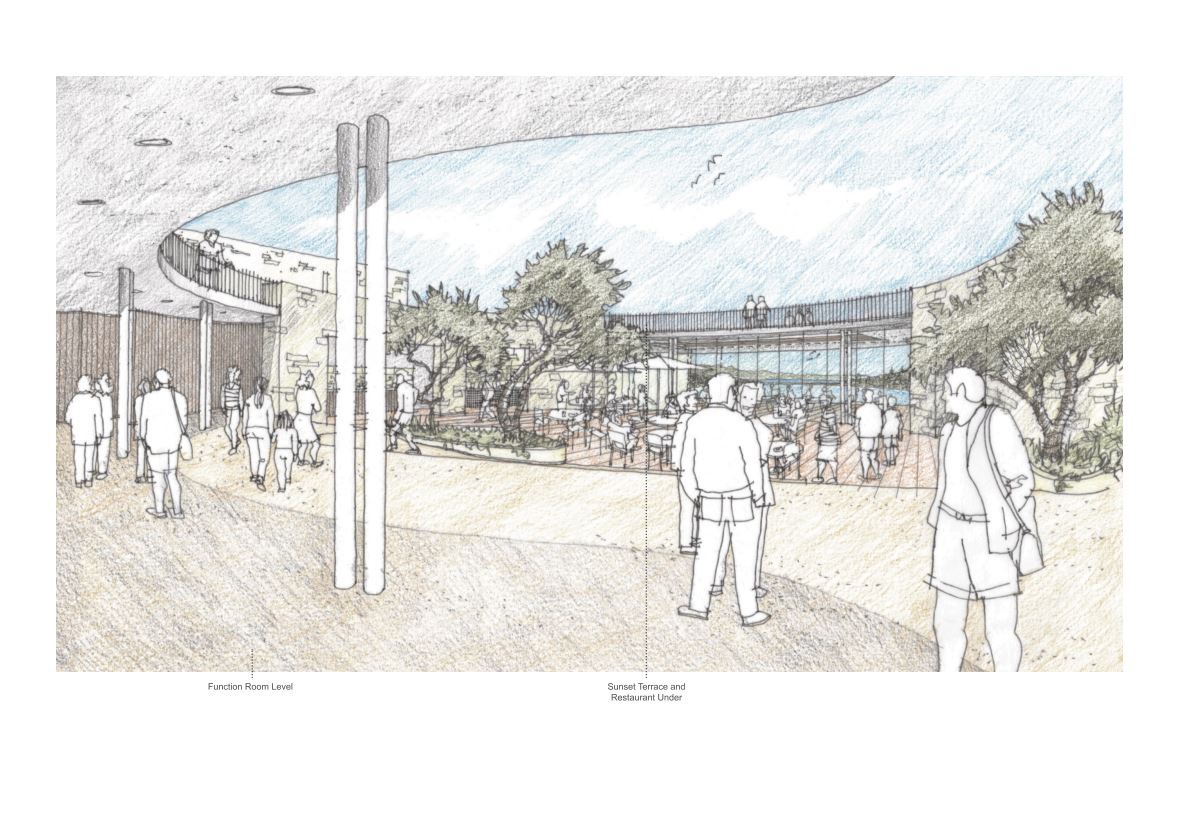

Our design embraces the concept of the collapsed former caverns that formed the salt lakes through the proposed ‘Sunken Cavern Courtyard’ space. This ‘Sunken Cavern’ space is pivotal to the success of the entire scheme and central to the ‘story telling’ of the site through built form to reinforce a ‘sense of place’ for the end users. When studying the site closely, it becomes evident that a limestone ridge, or embankment resulting from the former collapse of the Cavern, runs around the perimeter of Garden Lake, which has been an important driver in the layout of the site planning and placement of building mass in our proposal.

The design team have responded to the geological significance of Rottnest Island’s (Wadjemup) Tamala Limestone, which has been the subject of numerous significant studies relating to sea level change because of the unique tectonic stability of Western Australia. Further, the use of the insitu-limestone embankment as a component of a building’s wall, as is the case in the adjacent Assistant Gardner’ Cottage ruins (just outside of the site to the north), has inspired the proposed use of the remnant limestone rock from the cutting of the levels in the location of the proposed function rooms as the feature wall surface to the rear of the function rooms.

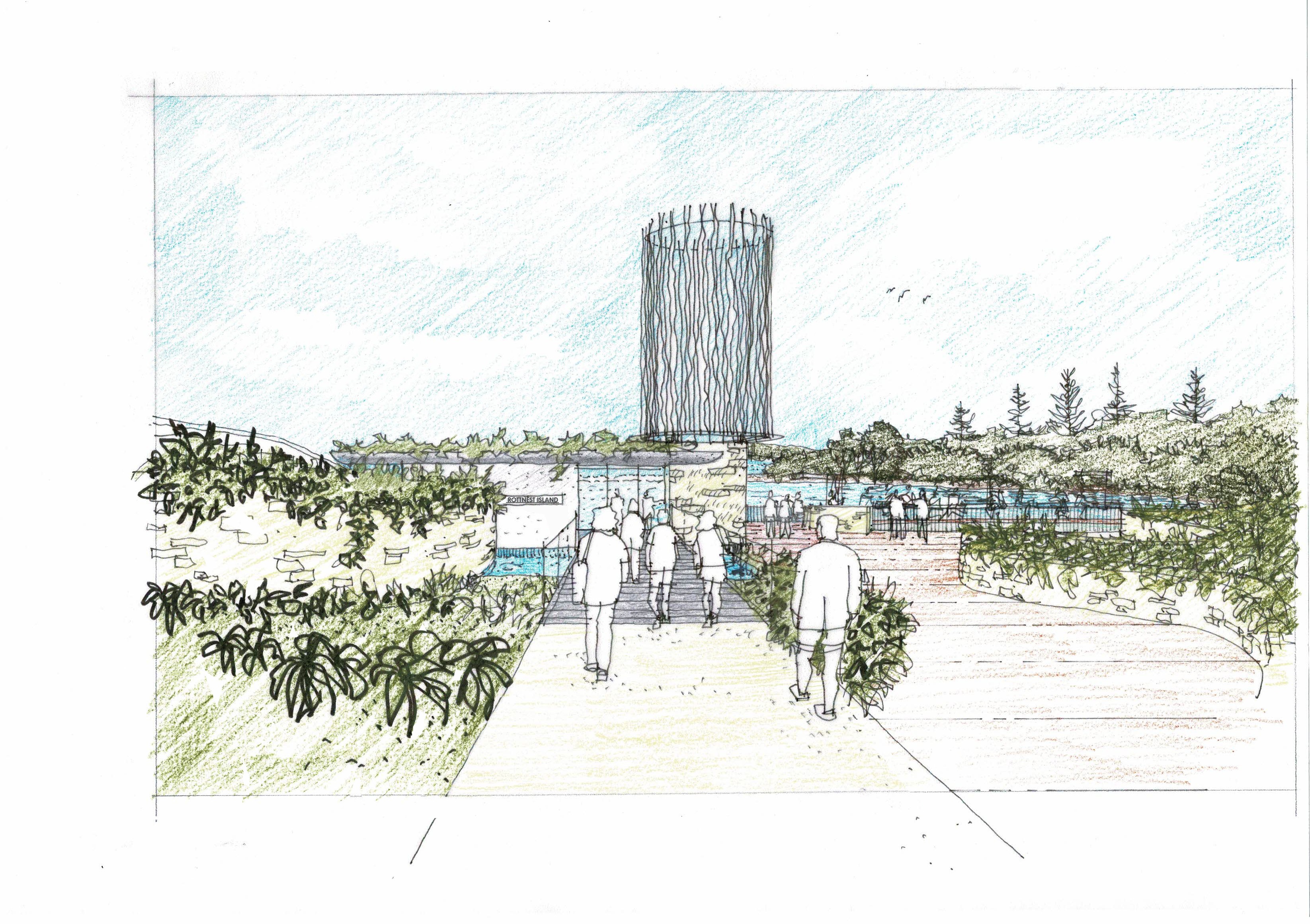

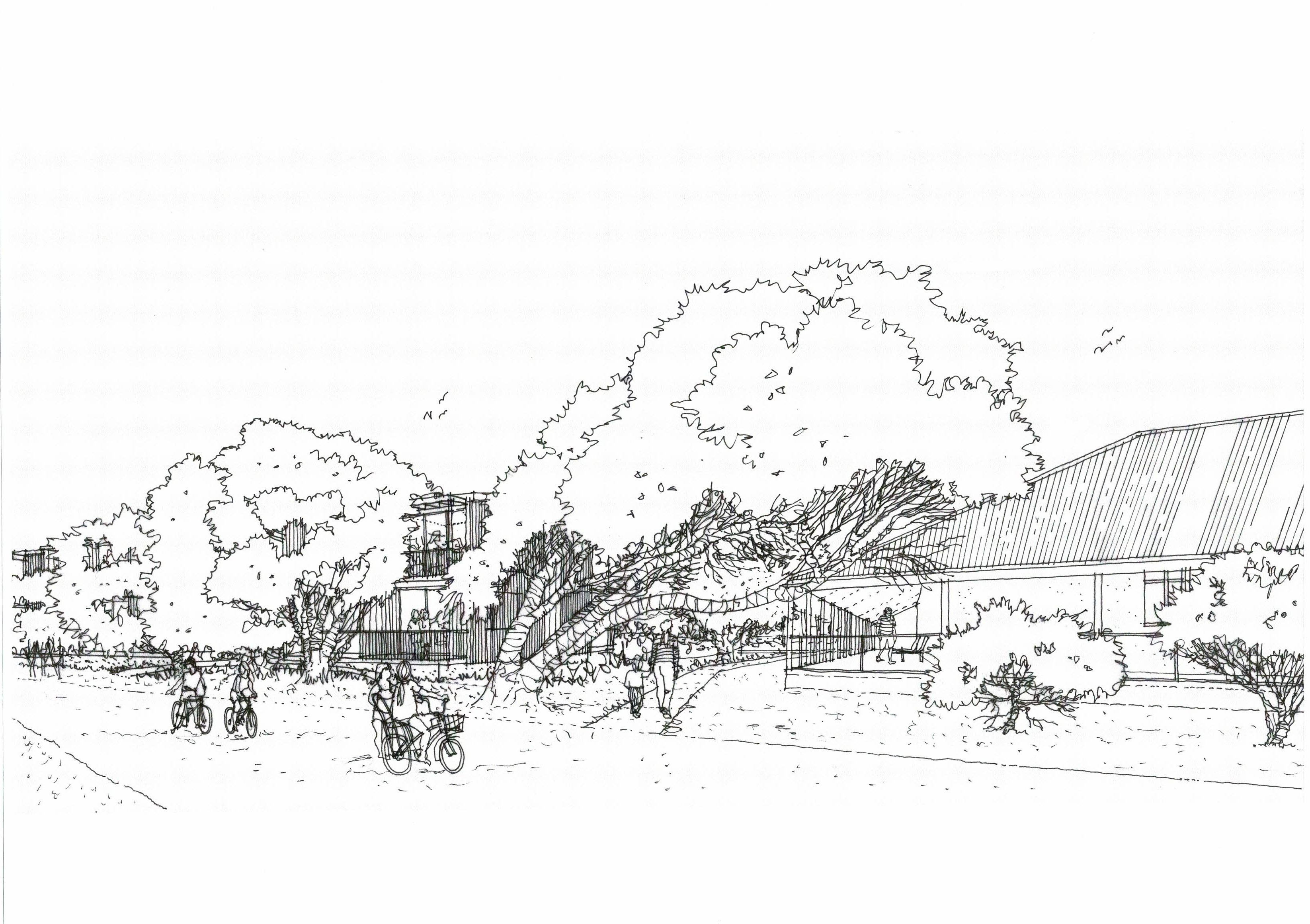

The resort entry is pierced by the Songline walkway that starts at Kitson Street and runs right through the entry lobby, visually connecting guests with Garden Lake to the west and the axis of the Songline to Wadjemup Hill and the West End beyond. The walkway that will be fabricated from a limestone concrete and will be finished flush with the adjacent paving, is intended to feel like a “Jetty Structure” will contain integrated artworks that celebrate the Whadjuk Noongar Songlines of the island.

Above the entry to the hotel and central to this precinct is the 12m high Sculptural Interpretative Entry Statement ‘Smoke Sculpture’ identifying the location of the Main Entry Lobby to the Rottnest Island Resort and acting like a beacon or marker for both guests and visitors from the Settlement to Wadjemup Lighthouse. Subtly lit the sculpture representing the ‘Welcome to Country’ Smoking Ceremony will welcome all to the Resort and symbolise our vision of a place for community gatherings, of spiritual healing and reconciliation between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people.

The former aboriginal prisoners on the island quarried limestone with picks in making the limestone blocks for the construction of the island’s early buildings. The adjacent Boys Reformatory and The Quod were constructed in this way. Evident to this day in the islands early buildings and in the quarries are the ‘pick marks’ left behind by the Aboriginal prisoners in fabricating the limestone blocks. The limestone wall component of the resort entry lobby is envisioned as a ‘solid block of limestone’ featuring the ‘pick marks’ and being seen as a linear ‘blade’ that further reinforces the dialogue of the Songline while acknowledging the existence of the Aboriginal prisoners on the island and their stone masonry.

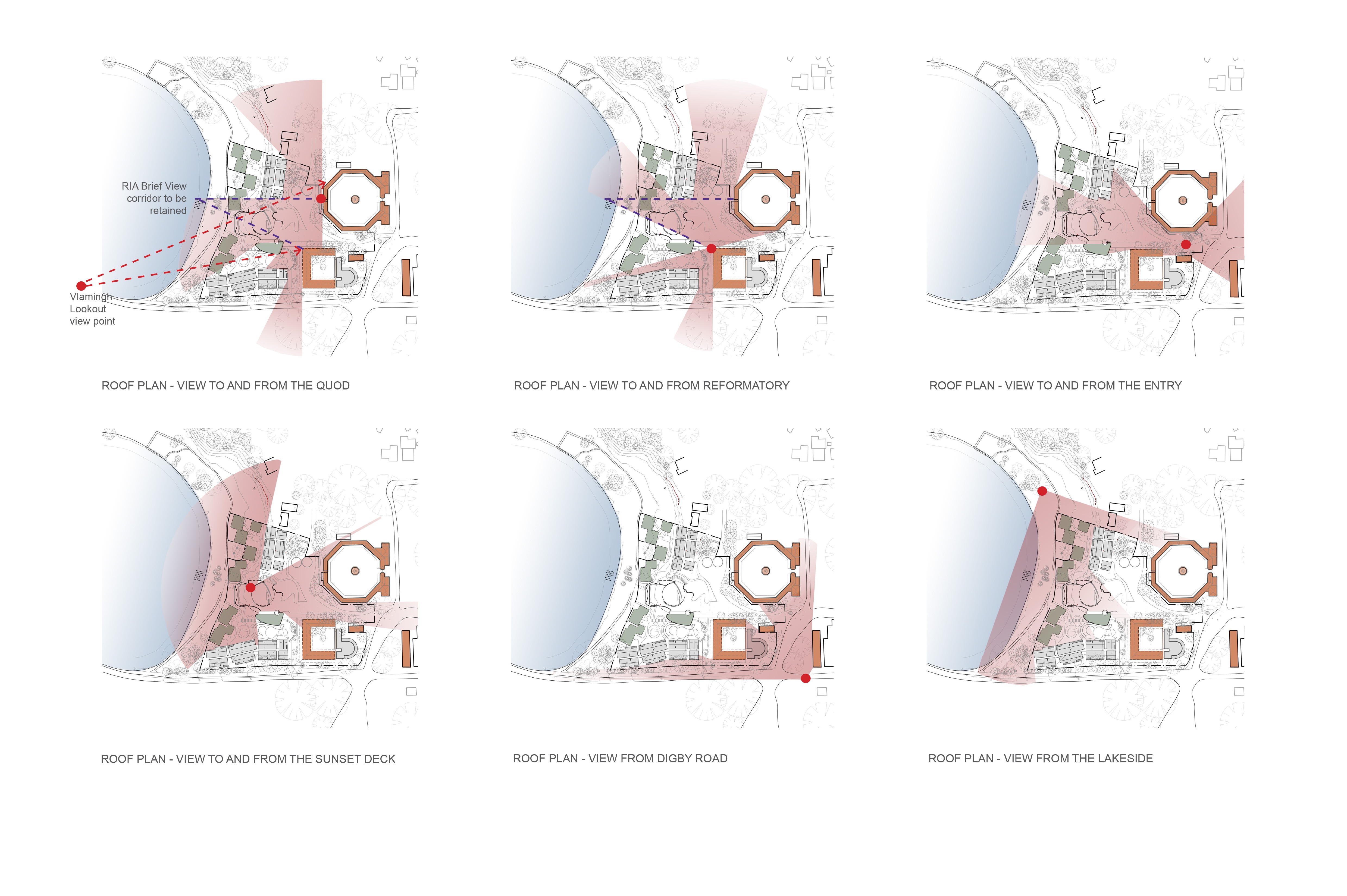

The scheme for the Rottnest Island Resort also responds to the many historical layers of the site, seeking to reinstate lost vistas and access, while referencing former functions and experiences through interpretative elements.

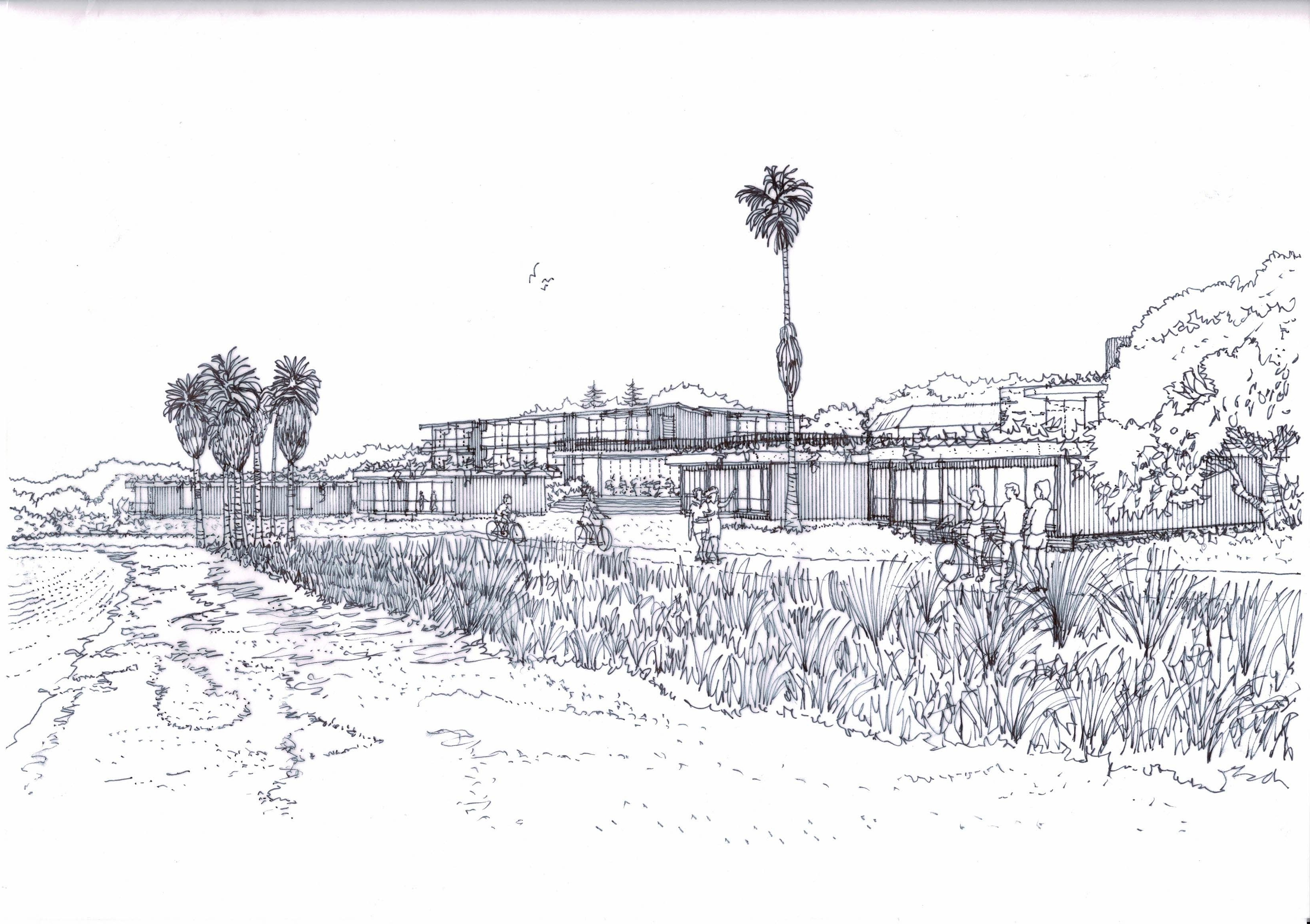

Our design acknowledges the garden history of the precinct and the notions of self-sufficiency that the former garden provided. This acknowledgement is reflected in the prominence of the landscaping through the central area of the site where ‘landscaping is primary, and buildings are secondary’. Further, the foreshore precinct within the site in the location of the proposed Garden Lake Villas, sees individual single-story buildings articulated to sit within a landscape. The Garden Lake Villas reflect the ethos of the ‘garden’ further through the proposed native grasses growing atop the roofs.

SUSTAINABILITY

Careful consideration was given to the specific climatic conditions of the site with the design of the project to suit local climate through smart and responsive design. A balance was found between the conflict of a substantial view out from the site to the west and the orientation required for the best solar and wind control.

The concept of the ‘Sunken Cavern Court’ stems from reflecting the geological history of the salt lakes adjacent to the site, with the real driver in providing the sunken courtyard space being a response to climate. Given the exposed nature of the site that is prone to the cold winds from the south and southwest, a solution was necessary to achieve outdoor spaces that would allow visitors and guests to be protected from the wind. The sunken courtyard is screened from the wind by the ‘cavern’ walls and the restaurant space. The restaurant can safely open the eastern glass doors to the courtyard, avoiding the negative aspects of a cold southwest wind. The ‘Sunken Cavern Court ‘peels back through the landscaped amphitheatre towards north, thereby allowing opportunity to adequately screen from the hot mid-day sun in Summer through the use of umbrellas, while allowing the warmth of the winter sun into the courtyard.

The proposed construction methodology of prefabricated components of building being transported to the island means that the prefabrication work is done within a controlled factory environment, waste is eliminated by recycling of materials, controlling inventory, and through the protection of building materials. Importantly, there will be minimal waste created at the building site. Modular building components can be disassembled in modules and relocated or refurbished for new use, thereby reducing the demand for raw materials and minimising the amount of energy expended to meet the new need.

Our proposal facilitates the protection of the sensitive lake foreshore environment through maximising prefabrication. Through the off-site prefabrication of building components, leaving only their assembly on site, the construction process provides less chance of contamination of the immediate area and in turn the lake environment through contaminated run off.

The project's energy requirements are intended to achieve self-sufficiency through the design and installation of power generation integrated with RIA’s existing power generation assets. The proposal includes incorporation of solar PV energy and a battery energy storage system (‘BESS’) as part of the projects energy solution. Surplus energy generated by the project’s energy assets shall be utilised by RIA, if desired – for example, any excess solar energy available following BESS recharging will be available to RIA’s electricity grid.

The design team shall incorporate ‘energy monitoring systems’ to allow the Rottnest Island Resort to be aware of, and respond to, real time feedback on the energy consumption of the resort complex to allow any necessary adjustments to minimise ongoing energy use.