Trafalgar Road, East Perth

Permanence, acoustics, apartments, lifestyle, outlook, gentrified, Goongoongup, Haig Park.

The Upper Eastside apartments sit at the highest point of the Haig Park residential development area where the 34 apartments in the building enjoy 360-degree views. The site was once a mulberry farm at the edge of residential allotments and bounding the East Perth cemetery. High standards were set for apartment finishes and communal facilities. The precast concrete building was designed to express depth, often lacking with purely functionary design when it comes to precast concrete. The apartment building delivered standards well ahead of it time with substantial floor areas, large dual balconies, lift lobbies shared between only two apartments per floor, each apartment with its own service zone accessible for maintenance from communal space.

The design service provided by Neil Cownie was holistic in the provision of the commercial feasibility studies, architectural design, documentation within a design / construct contract with Lendlease, interior design, along with coordination of the landscaping. Neil carried out this project while director at O&Z Architects.

CLIENT BRIEF

Client David Bertram set a very high standard for the quality of finishes, provision of services and generosity of the apartment spaces.

The site was within the East Perth Redevelopment Authority precinct and the design needed to comply to the Design Guidelines that had been set by the EPRA. Neil worked closely with the EPRA and client to obtain approvals for the development before embarking on the design development stage with client David Bertram. David was pivotal to the success in the project having introduced the then, Bovis Lendlease to the project following the design development stage of the design process. Working with Neil, David ensured that the ‘design development’ stage had been thorough to ensure that all materials, cabinetwork and key aspects of the buildings detailing had been resolved prior to creating the contract with the design/construct builder which ensured that the standard set at contract signing would not be diminished through the documentation and construction stages. Neil then worked with Bovis Lendlease in a design/ construct contract to deliver the project to completion.

The following is a statement from client David Bertram following the completion of the project: ‘Neil has excellent insight. He’s got a terrific eye for detail, and he gets the client brief. He also knows how to create spaces that are interesting, that create unusual elements and are not kitsch. It’s classical and elegant design. Neil has a wonderful knowledge of different materials and finishes and colours and how they will blend together to create some pretty amazing spaces. In Neil’s work you can see his sensitivity, his awareness, his reflection and his consideration. He takes the time to ponder and come up with a result that’s sympathetic to the outcome. He’ll work on it until he’s got exactly what he’s looking for. His bespoke approach is what I enjoyed more than anything. Just tell everyone to put their trust in him, he’s a great architect’.

HISTORY OF PLACE AND PEOPLE

Goongoongup is the name for present-day Claisebrook Cove and the surrounding area, encompassing an ephemeral freshwater stream that once flowed from the Perth swamps into the Swan River. The course of the stream drained east down Wellington Street and was joined by another tributary along present-day Royal Street. Highly significant to Noongar people, Goongoongup was not only a source of fresh water but a place to gather a variety of edible plants and aquatic life such as bulrushes and gilgies (freshwater crayfish). There is also evidence of fresh springs in this area.

The area remained an important camping place and food source for Noongar people right until the area’s redevelopment in the 1990s. It continues to be of great significance to Noongar people as a site that once linked freshwater springs, lakes and swamps (and their associated rich ecologies) to the Bilya (Swan River). Following the gradual resumption of land over time and the draining of the swamps by Europeans, water now flows into the Cove from a system of drains beneath the city. In 1995, the State Government adopted the name Goongoongup for the railway bridge constructed between the east river frontage and Burswood. (Source: Perth Museum).

As Perth began to expand, one of the obstacles to development was the Claise Brook valley with its intermittent flows and seasonal lakes. Claise Brook was an ephemeral freshwater stream which ran from Lake Monger through Lakes Georgiana, Sutherland, Irwin and Kingsford, and drained down Wellington Street to Tea Tree Lagoon at what is now known as Claisebrook Cove. Another tributary of the drain ran from Lakes Thompson and Poulett (Birdwood Square), through Stones Lake (Perth Oval) to join the mainstream at Water Street (now Royal Street).

The name of the waterway of Claise Brook and it’s cove was originally “Clause’s Brook”, after the ship’s surgeon aboard Captain James Stirling’s vessel that explored the Swan River in March 1827. Clause wrote about the area in his journal, but the first publication to mention Claise Brook was the Inquirer newspaper in 1848. The Inquirer announced that land at the mouth of the brook was reserved for use by a water mill. From the early 1850s, the area began to be known as Claisebrook after a convict depot was established in the area, rather than Claise Brook which chiefly referred to the waterway. According to Historian Richard Offen, the names seem to have been fairly interchangeable. (Richard Offen, 2016).

In 1885 most swamps at the back of Perth had been drained but Smith’s Lake and Lake Monger were still used for domestic water supply and the water from the main drain running into Claise Brook was used by residents living along its banks (Hunt 1980).

As the land was cleared of vegetation the water table began to rise and overwhelm the Claise Brook drain causing flooding in the town. The drain was expanded in 1899 to accommodate greater volumes.

In the 1880s it was still possible to catch gilgies (freshwater crayfish) in the Claise Brook drain, but by the 1890s a population influx meant that East Perth became very overcrowded. Two large open drains, with the city as their catchment area, flowed into East Perth where they joined together to form the Claise Brook drain. The stench of the drain became notorious, and it received waste from a tannery, soap factory, brickworks, factories, stables, laundries, four sawmills, and foundries. By the turn of the century the drain was considered a disgrace to the council and local children were warned not to go near it. One of the open drains in Coolgardie St was known as the ‘fever drain’ (Stannage 1979).

The East Perth Redevelopment Authority (EPRA) was established in 1991 to manage the redevelopment and urbanisation of the East Perth area. Former industrial land (including the former East Perth Gasworks, scrap yards, brick works, stables, warehouses and railway yards), has undergone extensive environmental rehabilitation and remediation.

Claisebrook Village now covers 137.5 hectares of riverfront land in East Perth. Claise Brook itself remains a drain buried beneath the city. 9Source: Museum of WA ‘Reimagining Perth’s Wetlands – Claise Brook the lost River of Perth’).

There is an incredible record of the first European settlers of Perth in the East Perth Cemetery that sits across the road from Upper Eastside at the site known as ‘Cemetery Hill’. A burial ground at the east end of the Perth district, Location R, now part of the East Perth Cemeteries, was assigned on 9 December 1829. Surveyed by John Septimus Roe the location of the cemetery seems logical, on a hill on the outskirts of town, but within walking distance up a steep sandy hill. The first acknowledged burial was on 6th January 1830 for John Mitchell, a soldier of the 63rd Regiment. It is believed there were at least three earlier burials, but this has not yet been confirmed. For forty years all Church of England burial services were conducted in either St George’s Church or the deceased’s regular place of worship. Architect Richard Roach Jewell designed St Bartholomew’s, a small mortuary chapel which was consecrated in 1871. Other denominations used their own churches or places of worship for the ‘celebration of death’ prior to the cemetery burial. In 1888 St Bartholomew’s Chapel became a parish church and was almost doubled in size after extensions in 1900.

The gold rush of the 1890s led to an increase in burials. Funerals were commonly held in a place of worship and later the funeral cortege would then move up Cemetery Road, a rough track that led diagonally up Wellington Street. Horses and hearses struggled in the sand so six bearers (rather than the traditional four) would take it in turns to carry the heavy coffin up the hill. As Perth grew so did concerns about the position of Cemetery Hill. There were fears relating to possible health hazards as “noxious matter will gradually drain down from the summit of the hill”. These concerns coupled with residential expansion led to the closure of the Cemeteries in 1899. There were no further burials except for those in existing vaults or with the approval of the Governor. This practice continued until 1916 with a handful of exceptions. In 1900 Karrakatta Cemetery became the main burial ground for Perth.

Through the 1920s and 1930s there was much criticism of neglect and vandalism at the East Perth Cemeteries, but little serious action was taken until many grave sites had been lost forever. In 1932 the site was declared a disused burial ground under the control of the State Gardens Board and its fate was uncertain during the Depression and war years. In the late 1940s headstones in poor condition were bulldozed, piled in heaps and removed. The Presbyterian, Jewish and Chinese cemeteries were relinquished, and the land made available to the Education Department. (Source: East Perth Cemeteries). If you would like to know more about the East Perth Cemetery, they have a wonderful interactive website and encourage visitors.

The site itself was once a mulberry farm suitably with a gentle fall down across the site to north within the Haig Park Municipal precinct. The Upper Eastside apartment building is within the East Perth redevelopment project which was an urban consolidation demonstration site constructed under the aegis of the Commonwealth Government’s Building Better Cities Program of the early 1990s. The Western Australian State Government created a land development agency – the East Perth Redevelopment Authority – to oversee the process of assembling ‘surplus’ government land such as rail yards and consolidating them into a 120ha developable site. The project was intended to demonstrate the feasibility and attractiveness of higher density inner city living to a then unconvinced private property development industry, and to remediate a polluted industrial site – an example of positive planning.

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Neil led the hard landscape design and worked alongside Andrew Baranowski of PlanE for the design development and delivery of the completed landscaping. The landscaping is all important from the ground level experience to the view down to the landscaping from the apartments above.

On arrival, guests experience the calmness of the entry area created through the simple landscaping of an ivy ground plane cover and a cop of deciduous trees. Recycled jetty timber bollards mark the edge between vehicles and pedestrians to the curb-less paving leading to the entry. On entry to the building, a directory board provides orientation before the central lobby separates into the two wings. Each wing features a Japanese inspired ‘Zen’ garden intended to exude a sense of calmness for guests and occupants of the building.

To the rear of the building the two ‘wings’ have separated to reveal a large central area garden. The concept of the rear garden is based on a celebration of the wetland history of Claisebrook stream and wetlands, where bridges span the ponds leading to places of private contemplation within the garden.

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

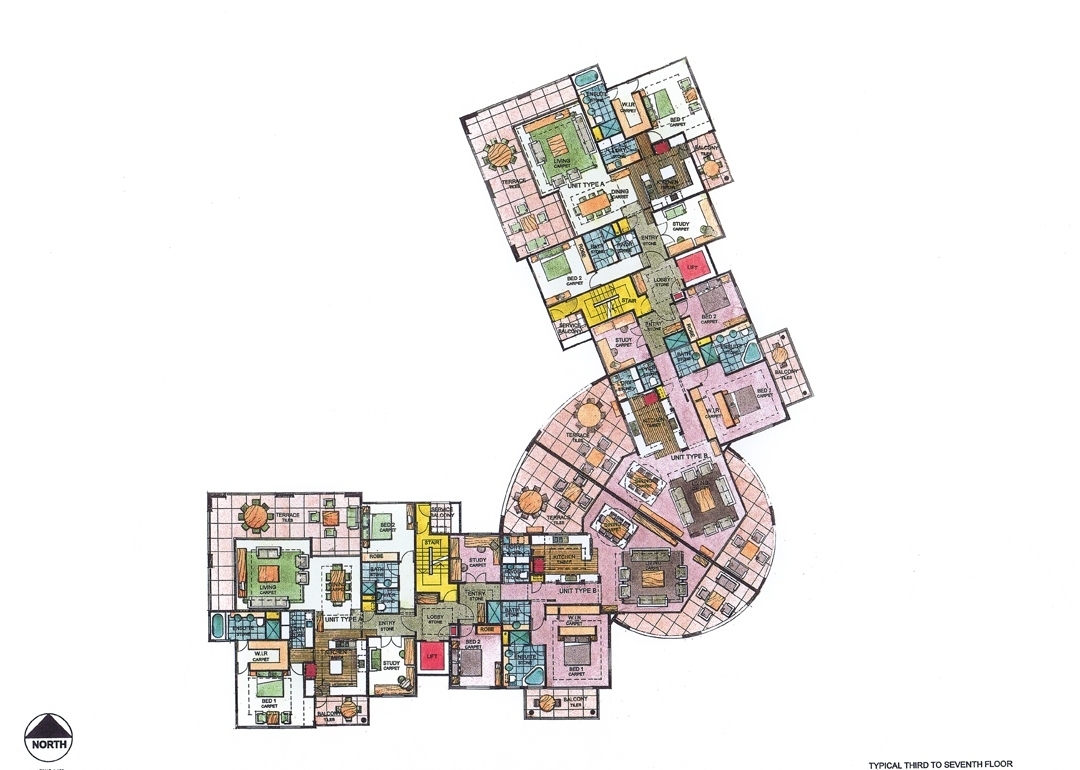

Above the basement parking sits an eight-story building that is mirrored centrally into two outstretched ‘wings’. Emphasis is given to the street corner where the circular plan form of the central balconies rise to the full height of the building to express the turning of the corner. The building mass in each wing is articulated to be viewed as two vertical elements capped at the ends of the wings with the pyramid shaped pitched roof. The incorporation of pitched roofs was a non-negotiable requirement of the East Perth Redevelopment Authority Design Guidelines which Neil did challenge several times before resolving to cap the ends of the building with the pitched roofs.

The precast concrete walls where edges could be seen, at locations such as balconies, were unusually designed to be 400mm thick, much greater than the standard 180mm thickness of precast concrete walls, with the intention that this would express permanence and solidity, usually lacking in conventional precast buildings. Sutle variations in paint colour help to articulate the mass into components of base, the two wings, end corners and the central drum.

The outstretched wings of the floor plan and the fact that each apartment has two, if not three opposing external walls along with two balconies on opposing sides of the building ensures access to the northern sun and excellent cross-ventilation provided to all apartments. The apartment plans provide generous space and functional layouts where internal and external living spaces flow seamlessly.

The materiality of the project is noteworthy, with real stone finishes to floor tiles alongside timber flooring, timber veneer cabinetwork and the robustness of the recycled wharf timber at key points within the communal spaces.

Another unique aspect of the design are the service areas that are accessed from landing levels of the stair wells. These service areas provide for two apartments at a time and house all of the service requirements for each apartment, alleviating the need for service access within apartment themselves.

SUSTAINABILITY

The outstretched wings of the floor plan and the fact that each apartment has two, if not three opposing external walls along with two balconies on opposing sides of the building ensures access to the northern sun and excellent cross-ventilation provided to all apartments. The apartment plans provide generous space and functional layouts where internal and external living spaces flow seamlessly.