Architect Ralph Drexel was my fourth-year studio master at the University of Western Australia. Ralph influences the way that I thought about design and the experience of the finished building.

The following is an essay that I provided for the 2023 Ralph Drexel Architect exhibition catalogue.

I have fond memories of Ralph and the supportive dialogue he provided as a fourth-year studio master at UWA. I can picture him now reciting some experience while simultaneously waving his arms in the air; a cigarette in one hand and his fingers wiggling wildly on the other; smoke circling him and wafting through the studio. His lessons were often implicitly woven into these tales of trouble. His objective seemed to be an expansion of our thinking rather than responding to or replanning the design issue at hand. These interactions proved to reinforce and enlighten, gently swaying our young minds through his anecdotes and analogies. These stories were usually off beat and always contained liberal doses of good humour. I recently reunited with Ralph in his home, and I posed to him that his work reflected his life as a storyteller; “that’s it, you got it,” he said, “I like that.”

Ralph was born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1935 to Austrian parents. His father was a ship’s captain and escaped the Nazis alongside his family. From Egypt the family moved to Kenya, where his father sailed on Lake Victoria. Seamanship was in the family with Ralph’s grandfather having been an admiral in the Austrian navy. Ralph proposes that his early immersion in Kenya and Egypt, where storytelling was a cultural core, was the cause for his narrative thinking. His life is peppered with remarkable stories; relocating to Perth aboard the ‘Moultan’ as a teenager in 1952, he was surrounded by returning athletes from the Helsinki Olympic Games. In his professional career, Ralph applied this unique understanding; recognising the ways stories construct a person, a client and a design. Each project took on an identity.

Initially, Ralph followed in the family tradition, with his first paid work being as a summer ‘deck hand’ for his father who was skipper of the Zephyr steamship - a ferry service on the Swan River along with trips to Garden Island and Rottnest Island at the time.

Ralph explained that on deciding to study architecture in 1953, he struggled to get accepted into the course due to his deficiencies in maths. This led to Ralph studying maths and physics at night school for a year while he gained practical architectural experience working in the office of Fred McCardell prior to being accepted into his first year of the architecture course.

Ralph commenced studying architecture in 1954 at Perth Technical College. His contemporary Colin Moore recalls that Ralph was already a proficient storyteller, while another peer Bob Gare fondly remembers Ralph’s stories as “more like ‘one liners”.

Ralph was taught by the likes of Margaret Pitt Morrison, Francis Senior and his own local architectural hero, John White.

Ralph’s passion for architecture was obvious even as a student. Bob Gare tells the story of the Perth Tech library;

The School of Architecture at Perth Tech had its own excellent library and librarian. The management at Perth Tech decided that they were going to amalgamate the architecture library into the main Tech library. The students didn’t think this was a great idea, particularly me, along with Ralph & Robin Kornweibel who decided, on the eve of the transferring of the library books to the greater library, to lock ourselves into the library overnight and move all of the architecture books into the church tower. We let ourselves out in the morning before it was discovered by the staff that the books had been ‘stolen’ and the police were called. John White who was a lecturer at Perth Tech did a great job of diffusing the situation and when the books were found the police took no further action. Unfortunately, our library ended up moving in any case.

Bob Gare also recalls a third-year design project that Ralph produced for an apartment building. According to Bob, Ralph was a proficient model maker and presented with floor plans and a scale model. Despite this, he was marked down for not submitting elevations.

Ralph was active in the student association of the day. He acted as editorial assistant alongside Bob Gare and Max Zuvela on the second last issue of the student publication ‘Aedicule Magazine’ in 1961, with John Cullen as editor.

Ralph recognised the importance of both the academic and practical aspects of his architecture studies; as he, like others, paralleled the course with experience working in architects’ offices. In his third and fourth year of the course, he was obtaining part time work experience with Forbes and Fitzhardinge. Here he worked on the original schematic design of the Hale School Memorial Hall with Tony Brand. The early scheme that Ralph had the opportunity to be associated with saw the building designed to be constructed from brickwork. When Gus Ferguson joined the design team fresh from experiencing the Beton brut works of Le Corbusier in Europe, the building transformed into a timber board marked in situ-concrete building.

The Perth architecture scene of the 1950’s was formed by a close community of students and architects. Ralph struck up an early friendship with older student Wally Hunter over a shared and continuing love for classic cars. Wally explained, “at the time there were only a few students in each year, so we ended up having friendships across all years while studying”. He further recalls that “the regular watering hole was the downstairs dive at the Palace Hotel where architecture students and architects would socialise. There were only 120 architects in Perth at the time and you would know them all. Another haunt of ours was the Shiralee Coffee lounge where Peter Parkinson would put on pantomime”. The Shiralee Coffee Lounge holds a special place in Ralph’s heart as it was there that his romance with his future wife Heather commenced.

While in their fifth year of studying architecture Ralph and Walter Hunter worked together in the St George’s Terrace based architecture practice of J.W Johnson. When working late they often made paper planes and threw them out of the window onto the Terrace below. One night they set a paper plane on fire and threw it out of the window, only to find it falling at the feet of a passing policeman. Other night-time pranks included drawing large question marks after the listed architect’s name on construction signboards for projects that they considered to be ‘dubious architecture’.

Despite the student antics, part-time work, night-time pranks and mathematical disadvantages, Ralph graduated and married Heather in the same year. The fun times and late nights working at the office of J.W Johnson were the catalyst for lifelong friendships which saw Walter Hunter the best man and Jim Johnson the groomsman at their wedding in January 1960. Obviously not forgetting to mention that this period marked the purchase of Ralph’s first classic old car- an Aston Martin.

Upon graduating, Ralph’s connection to the academic world continued after John White asked him to take on the part time role of first year studio master alongside Ian Molyneux.

Harking back to Ralph’s early emigration to Australia and his nautical past, he and Heather find themselves embarking for the first leg of their overseas trip from Fremantle port on Boxing Day 1961. Surrounded by drunken revellers and heading to Singapore, Ralph stands on the deck and looks below. Having been given a trumpet by Duncan Richards, Ralph pulls out the instrument to play Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, with the sun setting in the sky. As Ralph finishes and the ship begins to sail away, another trumpet starts to play in response from across the wharf. Ralph always does seem to have the best stories.

The plan was to take a self-drive overland tour all the way to London in a combi that was owned by fellow architects Barry Cameron & Binky Collins. Ralph and Heather arrived in Colombo, Sri Lanka some five weeks before the combi arrived, so they spent more time there than intended. The combi laid claim to a number of notable travel companions; Ralph and Heather were joined by Bob Gare and his wife Kate along with fellow Perth architects Binky Collins and Barry Cameron. Surprisingly, however, was that these six travelled simultaneously, sharing the driving and sleeping in one combi. The trip was punctuated with unexpected stops caused by the temperamental but enduring van. When in Bombay they caught up with Yossi Goldberg who joined them in taking in Le Corbusier’s work at Chandigarh, where the young architects studied and discussed every aspect of the master’s work. They drove on through Pakistan before driving through the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan then into Iran. Bob Gare recalls how Ralph had learnt to play the trumpet earlier in his life when he was in the army band during a period of National Service. Ralph had his trumpet with him on the trip and he brought it out to give it a blast as they drove past the army camps in Turkey in an attempt to bring the soldiers to attention.

By July 1962 they had successfully made it all the way to London. Ralph found work in the large London-based architectural practice, Farmer & Dark, before the same practice provided an opportunity for Ralph and Heather to move in employment with the practice onto Aden in Yemen. According to Bob Gare, Ralph spent most of his time in Aden drinking whisky and soda with the ‘Top Brass’ while working as an architect. While based in Yemen, they had their first child and Ralph bought a Sunbeam Alpine Series 1. After three years in Aden, Ralph traded in the Alpine for an Alpha Spider which returned with the Drexel Family to Perth.

Ralph’s 1965 return saw him begin work with Denis Silver of Silver Goldberg for a period, before moving on to work in the office of Ernest Rossen. While working for Ernest, Ralph took a major role in the conceptual design of the St Denis Church in Joondanna. Ralph recalls meeting with the American priest while developing the brief for the project, whom he describes as being a “cigar-smoking devil dodger”.

Outside of his day job through this period, Ralph teamed up with Julius Elischer, Darryl Way and John White to put together a scheme to present to the state government for a cultural centre to be built on Heirrison Island.

In 1966, Ralphed commenced working in the office of Summerhayes & Associates.

From the mid 1960’s to early in the 1970’s, Summerhayes and Associates grew as an office to considerable size. With a large office, Summerhayes’ relationship to the work altered and he was no longer as directly involved with design. Responsibilities were delegated to an echelon of associates, many of whom were selectively recruited by Darryl Way. Among them were Ralph Drexel, Binky Collins, David Melsom and Colin Moore. The group were responsible for the larger works of the late 1960’s which included the CBH building, 3-5 Bennett Street, and 2 Bindaring Parade’. (quote from Book ‘Summerhayes Architectural Projects’ 1993 UWA)

The CBH building is a personal favourite of mine, and I was determined to find out once and for all who was responsible for the design of the building. I interviewed Colin Moore who had worked alongside Ralph on the project at the time. The following is an extract from a previous interview of mine with Colin Moore;

‘Those were heady times in Perth, the sixties were exciting times. I was fresh back from London. Ralph was at the top of his game. Darryl Way had recruited various people, and he had this major project with enormous possibilities.

The basic concept for the CBH building was European design influenced by Le Corbusier. People have written about the building in terms of American influences, but I feel certain that the building was influenced by European design. The team was Ralph Drexel and Darryl Way doing all the early hard yards and then me coming along later with the task of having to do all the working drawings and get it up and running and built.

Darryl Way was enormously involved, his passion for that project was enormous. Far more than Ralph, far more than me, in getting that building built. Ralph was blessed almost with perfect pitch in a visual sense, he was pretty bloody good. He’d come in and say, “Well, what about we do this?” And you’d go and have a cigarette and talk it through. He was very gifted.

There were aspects of the design of the building that were not working, such as the design of the entry which was originally a bit understated. Famously, there was an enclosed plant room structure on top of the model. Someone knocked the model and the plant room form fell off and Ralph stuck it back on the model at the ground floor entry. “What about we do this as the entry?” We all agreed and that is what was built’.

When I reminded Ralph of the model of the CBH building he confirmed what was told by Colin Moore. As the plant room fell to become the entry, it was all just part of the story of that building.

Ralph says that he was ‘thrown in the deep end’ on starting work within the very busy office of Summerhayes and Associates. He recalls designing the 3 – 5 Bennett Street office building and then seeing his design sketches taken and built without any design development. The bold Bennett Street frontage read like two solid masonry blocks with the entry being located via the negative space between the blocks. To the street, the only windows were provided through a three story vertically proportioned bay window as part of the street front composition. To the south each floor was designed with floor to ceiling glazing with vertical masonry blades forming the gridded framework.

Within the office of Summerhayes & Associates, Ralph was responsible for the competition winning design of the successful City Arcade building. A building that provided a multi-level shopping arcade that contributed to the north/south pedestrian axis through the city. The design was intended to encourage ‘natural growth’ of the pedestrian network through the integration of adjacent properties into the City Arcade link. The central skylight and void allow natural light to filter down through all levels. The ten-storey office tower above the arcades has the gridded concrete modular sun hoods as a solution further developed from the CBH & Bennett Street buildings. The aspirational gesture of accommodating roof terrace landscaping, a childcare centre, roof top café and open air cinema at the roof area of the arcade remains an achievement to strive for today.

Ralph tells of an unbuilt design for the new Art Gallery of Western Australia that was proposed with an internal span of 120 feet. He speaks highly of structural engineer Peter Bruechle who came straight over to the office on hearing of a proposal for a building with a 120-foot span and discussed the design of the building for hours- “Peter was always up for a challenge”.

There was phenomenal creative opportunity for Ralph while working in the Summerhayes office, where he describes himself as having been provided with great personal freedom.

Despite being made an Associate of Summerhayes & Associates after the success of the competition winning design for the City Arcade building, Ralph had had enough and moved on in 1969 to work with Forbes and Fitzhardinge.

Ralph says that he made the most of his time working in the office of Forbes and Fitzhardinge, but he lacked the design freedom that he had previously when at the office of Summerhayes.[Kw2]

Ralph designed a new house for his family which began on site in 1968 with Ralph as the owner / builder after a protracted approvals period. They moved into the completed Kingsway Street, Nedlands house in 1969 which had five flights of stairs up to the flat roof terrace to take in a view to the river. Ralph tells of entertaining the client for the City Arcade project in the completed house on a wet winter’s day, water was seeping down the internal walls of their living room as the client asked Ralph if all his buildings leak like this. Ralph responded with “not all of the time”. Ralph has fond memories of this family home in which they stayed until 1981.

Ralph had been supporting his architectural practice with part time teaching at the WAIT School of Architecture until about 1970 when WAIT provided Ralph with a two-year contract. Prior to the end of this contract Ralph was approached by John White from the School of Architecture at UWA to take on a twelve-month contract teaching fifth year students. Ralph said that “at the time you could write reports for the University, and you were only permitted to make a maximum of 20% of your income outside of the University, that was ok for me as the money that I was making outside of University didn’t amount to much anyway.” [Kw3] Ralph’s preference to remain in practice while on staff was challenged by the University as it was unusual to do so at the time. Ralph was indebted to Professor Hugo Brunt whom supported Ralph’s desire to remain in practice while teaching, stating that you actually have to do the work- not just write about it.

In 1971, Ralph teamed up with Walter Hunter parallel to his teaching job at UWA, to submit a scheme in the competition for the new High Court in Canberra.

Ralph developed good relationships with some of the senior students that led them to find employment with Ralph upon graduating. One such student was Ross Donaldson, who reflects on that time as being “very influential for me at a critical time when I needed someone who believed in architecture”. Ross would also go on to teach at UWA, from 1977 to 1997. In 1979, Ralph and Ross worked together on a scheme for Parliament House Canberra competition.

Ralph continued at UWA and his own architectural practice until 2000 after an astounding 26 years of teaching.

Ralph joined his long-term friend Walter Hunter in the office Walter Hunter Architect for the series of chapel & crematorium buildings and other works for Karrakatta Cemetery, projects that Ralph describes as being ‘houses for the dead’. Ralph tells of the importance of allowing an experience of ‘procession’ for mourners, giving them time to safely contemplate while walking on a continuous flat surface without steps, as both young and old would drag their feet in the walk to the chapel. The two Karrakatta chapels were designed to work together, with the space between forming part of the meaningful experience. Ralph says; “the curved wall was intended to connect internal and external spaces as the eye was drawn to the exterior to see landscaping, birds and butterflies, making a connection with nature for mourners. Internally the curved wall is punctuated with small openings and a glimpse through the opening to a stair, intended to reinforce the feeling that you were outside”. I have experienced that funeral chapel more times than I would like and always feel as though the design was intending the openings in the wall and the glimpse of a stair to suggest another world beyond the wall. Ralph’s description of his motivations for the design only proved to me his incredible capabilities to understand and translate human experience.

Walter describes the process of design between himself and Ralph as a collaborative and also influenced by the landscape architect Peter Carla. Walter explains:

The double height wall on the right-hand side of the main chapel at Karrakatta conceals the existing crematorium. The design solution for the chapel was simply using the space left over between the existing buildings on the site. The Karrakatta chapel was shaped by the site’s own history. The 1998 Pinnaroo Funearaly Chapel on the other hand was a response to the location and the bush site- it was in ‘limestone country’. When looking at Ralph’s earlier 1981 design for the Anglican church in Thornlie, you can see where the concept for the courtyard forecourt at the Pinnaroo Chapel had its origins. The colonnade to one side of the courtyard allows mourners a place to gather and experience procession on their way to the chapel, as was the design consideration in the Karrakatta Chapels.

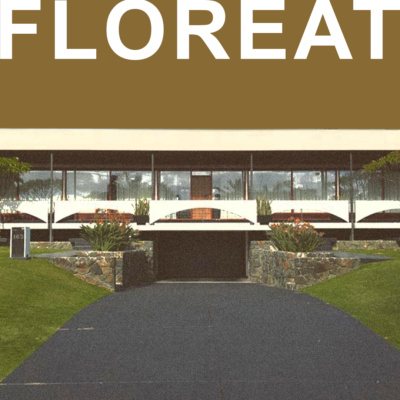

Ralph designed many homes throughout his career, exploring new stories and solutions for each project. Ralph explored internal void and volume within the perimeter container as in the 1970 design for his own house & the 1974 Lilleyman House, Nedlands; courtyard houses such as the 1970 Beck House, Caversham; simple extruded barn like forms, such as the Howle house in Victoria Park 1979 & 1980 Noble House; tower like houses such as the 1991 Pratt House additions, Shenton Road, Swanbourne & 1980 Negus House, High Street, Marmion; organising curves in plan layouts such as the 1995 Sadaka House, City Beach and the 1996 Blaike Ledbedek House, Floreat and suspended structure as in the 1991 award winning Koeppe Street additions along with the Packenham Street, Fremantle warehouse conversion and again, in the Sadaka House. The 2010 Armstrong House manages to reference a whole and impressive host of architectural periods.

Ralph’s work reflected the ever-evolving architectural language of the time. Bob Gare tells of Ralph’s love of Le Corbusier’s work and refers to Ralph as being ‘the best Perth architect of his time’. The influence of Le Corbusier is certainly evident in the design of the CBH building, Bennett Street building, St Denis Church and the design for the High Court competition.

Colin Moore reflects, “at the time everything in the local architectural scene was painted white and it was all about the solidity of the wall with small openings, when you compare the work of say Julius Elischer and that of Ralph through the same period, the work done by Ralph used the same devices but produced work that was more romantic, stemming from a pure emotional response. Ralph was the classic upfront designer with a lot of flair who wasn’t fussed by the detail, whereas Julius was concerned with the detail”.

It is interesting to compare the houses designed by Ralph with the aspirational goals of the City Arcade project, where light filled voids, integration of building with landscape and the use of roof terraces permeated through to the design of his individual houses.

Ralph designed a new house in Sadka House, Challenger Parade, City Beach and remains one of my own favourites and a house that received an RAIA Architecture Award for Single Residential Projects in 1996. Ralph describes his clients for this project as being gentle and cautious people. The interplay of mass and void in this house is something that I find consistent through Ralph’s work. The two-storey high curved wall on the southern side of the house is a visual expression of protecting the house from the prevailing winds. A boardwalk penetrates the wall, where an opening in the curved wall is capped with a masonry sphere, and the boardwalk continues in a protected courtyard to the entry. Ralph’s greatest delight in describing this building comes from the unexpected; “sand blew beneath the front door and etched a beautiful texture on the timber floor”. He describes the house simply as an “inside/outside house with a protected north facing outdoor area”.

Armstrong House in 2010 was the last house that Ralph designed. His clients felt that Ralph interpreted their 150-page brief well, however, Ralph admitted that at that stage in his career, his design responses were more intuitive than that of responding to a detailed brief. After decades honing his skills for design and consultation, he recognised and prioritised his intuition. The house looks internally to its two courtyards as the architecture seems to reference everything from Corbusier’s Ronchomp, architectural details of the Middle East & Japan and Mediterranean roof terraces. It feels fitting that his last build drew upon Ralph’s greatest strengths; an incredible gift for design, the ability to translate feeling into the physical and an integration of diverse cultural storytelling through architecture.

Following a series of interviews with Ralph, he left me with this statement; “architecture is a three-letter word… joy”.

From Egypt to Yemen, burning airplanes flying through the city to boats crossing international waters, and buildings that seem to breathe with life; Ralph Drexel has led what I can only describe as a life in perpetual motion; filled with architecture and synonymously, joy. His love of classic cars suddenly seems to make perfect sense.